Long years ago, in ages crude,

Before there was a mode, oh!

There lived a bird, they called a “Dude,”

Resembling much the “Dodo.”

The World (New York), January 14, 1883, page 9.

[i]

These words, the opening lines of Robert Sale-Hill’s poem, The True Origin and History of “The Dude,” introduced the world to the word, “Dude.” The poem reads like a natural history lecture, describing the habits and habitat of an odd bird, the “Dude.” The “Dude” had a “feeble brain,” wore “skin-tight” pants and a “pointed shoe,” and put on British airs.

A few months earlier, a humor piece entitled, Natural History (first published in June, 1882), described the behavior of the “Dodo;” a “soft headed young man” who affected an English accent. A poem based on the story, Dodo, elaborated on his brain, pants and shoes:

“What is that, mother?”

“The dodo, my child;

His thoughts are weak and his brain is mild.

. . .

He wears lean pants and tooth-pick shoes,

And hasn’t an ounce of sense to lose.

Look at him close as you see him pass,

He looks like a man, but was made for an ass.”

– Hawkeye

National Republican (Washington DC), August 24, 1882, page 4.

Brain, pants, shoes, Anglophile.

D-O-D-O / D-O-O-D / D-U-D-E

Coincidence? Hmmm???

Background

Gerald Cohen (the editor of Comments on Etymology), Barry Popik (proprietor of the online etymology dictionary, The Big Apple (

barrypopik.com)), and others have established, with a high degree of certainty, that the word “Dude” first appeared in print in

The World, on January 14, 1883.

Despite ridiculously thorough efforts to find evidence of earlier use, all roads lead back to that date.

Several apparently earlier attestations, in which “dude” was tossed out casually as though it were already a well-known, established word, have all been shown to have been inaccurately dated, or intentionally misdated.

[ii] The explosive success of the word in the immediate aftermath of the poem also suggests that the word was previously unknown.

Although the word is nowhere to be found before the poem was published, hundreds of stories, poems, songs, and articles were penned within just a few months after its publication, all ridiculing the witless, arrogant, useless “dude.”

A “Dude,” as described in Sales-Hill’s poem, as well as in hundreds of descriptions of dudes from the dude-craze of 1883, is a very specific “type,” with very specific clothes, and very specific behaviors. A “Dude” was, generally, an effeminate, young Anglophile, in the mold of Oscar Wilde. He affected a British accent and manners. He was fashionable, but not flashy. He wore tight pants and pointy shoes. He wore a jacket with long tails under a short overcoat, with tails hanging out the back. He carried a silver-tipped cane, wore a derby hat, and a monocle. Dudes were aloof. They were rude. They hung out around stage doors and dated actresses; but they were not particularly nice to them. And, above all, they were vapid and stupid.

Although the “type,” and the associated fashions, existed before 1883, was no word to describe the new “type,” specifically. The older words, “dandy,” “fop,” “swell,” and others in a long line of similar terms, were considered inadequate. Dandies, fops and swells were extravagant in their fashion and manners, whereas dudes were understated.

The old race of fops, dandies, and swells enjoyed life, though perhaps in a misdirected way. There is no evidence that the dude enjoys life at all.

The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, March 6, 1883, page 3, column 3 (citing the New York Post).

So, where did the word come from? Similarities between the story, Natural History (of the “Dodo”), and Robert Sale-Hill’s poem, The History and Origin of the “Dude,” suggest a possible link between “Dodo,” as used in 1882, and, “Dude,” coined in early 1883. “Dude” may also have been influenced by words like “fopdoodle,” “Fitzdoodle,” “Fitznoodle,” and “doodle,” all of which had been used to describe dude-like characters, long before “Dude” was coined.

The History and Etymology of the word, “Dude”

If “Dude” was coined on January 14, 1883, the question remains; was it plucked from thin air, or borrowed from an existing word or expression. And, if so; what were those words or expressions?

Speculation about the origins of “Dude” is nearly as old as the word, itself:

Whether it is vulgarly and ungrammatically derived from the verb “to do” and is indicative of the frequency with which the youth belonging to the class in question is taken in and done for, or whether it is a bold attempt to foist the extinct dodo upon us by a shallow transposition of two letters, is a mystery.

New York Mirror, February 24, 1883, pages 2/5 (referenced in Comments on Etymology, Vol. 43, no. 1-2, page 35).

THE DUDE,

Being in Fact the Latest Society Dodo.

The Evolution of the Same.

N. Y. Post.

When a foreign term is suddenly naturalized we may be sure that there is something in the atmosphere of the place of adoption which makes it convenient and useful. Dude is said to be originally a London music hall term, but it has been transplanted here, and its constant use shows that it is for some reason well fitted to take a permanent place in the vocabulary of fashion.

The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, March 6, 1883, page 3, column 3.

The Dude.

The New York correspondent of the Brooklyn Eagle, a sort of “Man about Town,” notes the introduction of a new word into the language. It is d-u-d-e or d-o-o-d, the spelling not having been distinctly settled yet. Nobody knows where the word came from, but it has sprung into popularity within the past few weeks, and everybody is using it.

The Daily Astorian, March 28, 1883, page 1, column 1.

If the Springfield Republican is to be credited the word “dude” (pronounced in two syllables) is not a new one and is not of English origin. It has been used in the little town of Salem, N. H., for twenty years past and it is claimed was coined there. It is common there to speak of a dapper young man as a “dude of a fellow,” of a small animal as a “little dude,” of a sweetheart as “my dude,” and of an aesthetic youth of the Wilde type as a dude. But how the word attained so sudden and widespread a notoriety puzzles Salem. Its revival at New York is credited to a disgusted Englishman, who remarked, after visiting a rich club, that the young men were all “dudes.”

National Republican, April 14, 1883, page 4, column 7.

[iii]

Current Views of the Etymology of, “Dude”

Recent efforts to trace the etymology of “dude” focused on the purported use of two-syllable “dude” (doody) in Salem, New Hampshire, as first suggested in the Springfield Republican, and reprinted widely elsewhere. Barry Popik and Gerald Cohen used a single newspaper article from 1879, in which a curly-haired boy was taunted with the words, “Sissy” and “Yankee Doodle,” to connect the dots from “dude” to “Yankee Doodle,” via the two-syllable “dude” (doody) of Salem, New Hampshire.

“Dood” of “Yankee Doodle (Dandy)” is almost certainly the source of 19th century dude, probably via the shortening of ‘doody’ . . . .”[iv]

Although “Yankee Doodle” had previously been regarded as a possible origin of “dude,” the discovery of the 1879 article was the first indication that “Yankee Doodle” had ever been used in a manner consistent with the original meaning of, “Dude.”

Critique of the Current View

Information uncovered since Popik and Cohen published their article raise questions about the strength of the findings. When their article was published, they were still haunted by the specter of at least one purported pre-1883 attestation of “dude,” in Mulford’s Fighting Indians(2nd, ed.), which was believed to have been published in 1879. That reference, however, has since been shown to have been published much later. Robert Sale-Hill’s poem now stands alone, as the only attestation of “Dude” before the Dude-craze of 1883. All later references to “Dude” seem to owe their existence to the original poem.

If “Dude” was coined in January 1883, it may not have developed organically, from an earlier expression, in a linked chain of natural language development. It may be wholly unrelated to two-syllable “dude” (doody). And in any case, if Robert Sale-Hill did coin the expression, there is no clear connection between him and the town of Salem, New Hampshire, where two-syllable “dude” is said to have been used before 1883.

In reaching their conclusions, Popik and Cohen relied on a version of the two-syllable “dude” (doody) article from

Clothier and Furnisher (volume 13, number 10, pages 27-28) that described the geographic range of two-syllable “dude” (doody) as, “some New England towns;” not as “the small town of Salem, N. H.,” as specifically mentioned in most of the dozens of other versions of the article in other publications.

Most of those sources credit the

Springfield Republican as the ultimate source of the information.

It seems likely that

Clothier and Furnisher’s version was a paraphrased version of the original, or a reprint of paraphrased version of the original article.

The apparent overstatement of the range in which two-syllable “dude” (doody) was used may be significant.

Versions of the same article were published in several towns in New England.

[v] In each case, the article was published without any mention, or apparent awareness, of the existence of the word throughout New England, generally.

If two-syllable “dude” (doody) was used in New England before 1883, it was not very widespread, and may have been confined to the immediate vicinity of “the small town of Salem, N. H.”

Robert Sale-Hill, the author of

The History and Origin of the “Dude,” was not from New England.

He was from old England.

He was an Irish-born Englishman who lived in New York City.

He was an amateur actor who frequently performed at charity events, a sometimes poet, a cricket player, and frequent ladies man.

He publicly abandoned at least one fiancé, and was believed to have abandoned several fiancés before getting, “’actually married,’ as a young lady pensively remarked”

[vi]on the occasion of his first wedding.

As an Englishman, he did not have to affect an English accent, but his accent was not exactly English, either.

A review of one of his performances complained that he had, “an indistinct utterance which is neither English nor American.”

[vii]

Although his life in New York City appears to have been that of a real “Dude,” he came from a long line of adventurers and soldiers. His grandfather, Major-General Sir Rowley Sale (GCB), led the defense of Jalalabad in 1841. His grandmother, the Lady Sale, was held hostage by the Afghans and published a diary of her experiences after she was rescued in dramatic fashion by her own husband. His father was a Captain in the Bengal Irregular Cavalry at the time of his death, in 1850, when he was only one month old. His brother, Lieutenant-General Rowley Sale-Hill, served as a “distinguished officer of the Bengal army.”

But Robert Sale-Hill did not stay in his soft, New York cocoon forever. He eventually earned his macho “bona fides” out West. In the 1890s, Outing magazine published his dramatic accounts of hunting adventures in the Rocky Mountains. He lived in Helena, Montana, in 1889, where he was apparently a successful real estate investor. By the early 1890s, he had moved to Tacoma, Washington, where he was one the leading lights in the city. He served as Vice President of an electric company, performed in amateur theatrical productions, and attended society events organized by his wife. By 1909, however, he was back in England, where he worked as an executive at Brown Brothers bank. He died in 1920.

![]() |

| Robert Sale Hill, Serious Thoughts and Idle Moments, Frontispiece, 1892, Private Printing. |

If Robert Sale-Hill coined the word, “Dude,” as the evidence suggests, he could just as easily plucked the word out of thin air, as have resorted to an obscure, micro-localism from Salem, New Hampshire. Although the two-syllable “dude” (doody) origin story is plausible, standing alone, it does not easily explain how, or why, Robert Sale-Hill came to adopt the word for his poem. It is possible, I suppose, that he could have heard the expression from a friend from New Hampshire, during a trip through New Hampshire, or from one of those women to whom he had been briefly “engaged.” He could then have intentionally altered two-syllable “dude” (“doody”) to one-syllable, to fit the meter of his poem, or to rhyme it with “crude.”

The fact that there is only one single known use of “Yankee Doodle” as a dude-like insult may also suggest a tenuous connection between “Dude” and “Yankee Doodle.”

If the two-syllable “dude” (doody) story were the only plausible explanation, it might seem satisfactory. But new evidence, and changed circumstances suggest another origin.

A New Etymology of Dude

I propose a new etymology of “Dude.” Several striking similarities between Sale-Hill’s, The History and Origin of “The Dude,” and the story, Natural History (and the poem inspired by the story), strongly suggest that the earlier story and poem influenced the later poem, or at least that the use of “dodo” illustrated by the earlier story and poem influenced the development of the word, “Dude.” The use of “dodo” to describe a dude-like character was consistent with a long-standing practice of using bird-related imagery and metaphors when writing about fashion conscious men. Even “Yankee Doodle” stuck a feather in his cap.

The word “Dude” could also have been influenced by “Yankee Doodle,” but the fact that only one such reference has been found makes the connection seem remote. In the mid-1800s, however, there were another “doodle” and “-oodle” words that may have influenced the word, “Dude.”

“Fopdoodle” (or “fop-doodle”), which dates to the early 17thcentury, is one of a succession of words, including “dude,” that has been used to describe an effete, fashionable man:

Fops by whatever phrase designated, whether as “fops” proper, “beaux,” “macaronis,” “sparks,” “dandies,” “bucks,” “petits maitres,” “Bond Street loungers,” “exquisites,” or “Corinthians,” have well nigh vanished from the world. Their very names have become enigmatic. To trace from age to age through all its phases of development the history of these popinjays of fashion were a task not unworthy of satirist of philosopher . . . .

Charles James Dunphie,

The Splendid Advantages of Being a Woman, New York, R. Worthington, 1878, page 72.

[viii]

Although “fopdoodle” was already considered archaic in the 1880s, it still appeared in print regularly; notably in a poem from 1881 in which a “Dandy” is referred to both as a “rara avis” (rare bird – like a dodo) and a “fopdoodle.” The title, “Lord Fopdoodle,” was also regularly used to denote fancy-pants noblemen or Englishmen in comedic and satiric writing. Other last names, apparently derived from Fopdoodle (Fitzdoodle, Fitznoodle, and Fitzboodle) were also frequently used in comedic and satiric writing in England and the United States to refer to silly dandies, Englishmen, or wealthy businessmen.

A “Dude” may be a “Dodo,” but he may also be a Fopdoodle, Fitzdoodle, or Fitznoodle. “Fopdoodle,” which predates “Yankee Doodle” by more than one-hundred years, could have influenced the origin of “Yankee Doodle,” as well. When Yankee Doodle stuck a feather in his cap, he called it, “Macaroni;” another word denoting a fashion-conscious young man dating to about the same time as “Yankee Doodle.” If “Fopdoodle” did influence “Yankee Doodle,” perhaps “Dude” and “Yankee Doodle” are more in the nature of linguistic first-cousins, than parent and child.

A Dude is a Dodo

Anatoly Liberman, writing on the Oxford University Press’ OUPBlog, wrote that the assertion that “Dude” was derived from “Dodo” as one of the, “wild suggestions [that] have gone a long way toward fostering the opinion that etymology is a pursuit worthy of only the stupidest dudes (duds).” If that is the case, I may be a stupid dude. I propose that “Dude” was coined, at least in part, from the word “Dodo.”

The theory is nearly as old as the word “Dude”:

Whether it is vulgarly and ungrammatically derived from the verb “to do” and is indicative of the frequency with which the youth belonging to the class in question is taken in and done for, or whether it is a bold attempt to foist the extinct dodo upon us by a shallow transposition of two letters, is a mystery.

New York Mirror, February 24, 1883, pages 2/5 (referenced in Comments on Etymology, Vol. 43, no. 1-2, page 35).

The Dudus Americanus, or American dude has of late been the subject of much scientific inquiry. It is held by many that the dude is the descendant, through a long course of evolution, of the dodo, because of the similarity in name and because the dodo strutted about as though it were pleasing to look upon, whereas it was ridiculous in appearance. Moreover, the dodo is described as “stupid and incompetent.”

The Sun (New York), April 27, 1883, page 2.

Dude – There surely could be no great violence done to rules of linguistic science if we were to connect this word with doodle or fop-doodle, a fool or fop. The plant doodledoo (Vol. iv, p. 82) appears to be so named from its flaunting colors. (Cf. Cock-a-doodle-doo.) Skeat, in discussing the word dodo (Port. Doudo, a dolt, a fool), compares it to the English dude (“Etym. Dict.,” p. 800).

American Notes and Queries, Volume 4, Number 12, January 18, 1890, page 137.

The fact that “Dodo” has been left out of the discussion is surprising, perhaps, because the word is right there in the opening lines of Robert Sale-Hill’s poem:

Long years ago, in ages crude,

Before there was a mode, oh!

There lived a bird, they called a “Dude,”

Resembling much the “Dodo.”

Was “dude” derived from “dodo,” or did Sale-Hill use “dodo” because it was funny and fit into the rhythm and rhyme of the poem?

The genus and species of the dodo bird is

didus ineptus.

[ix] Ineptusmeans foolish, silly, inept, absurd, or senseless in Latin.

Didusappears to be a have just been back-formed into Latin from

dodo.

The plural form of

didus is

dididae, and the adjective is

didine.

Transpose the letters d-o-d-o to d-o-o-d and you’ve got “dude.” Dodo: scientific name – Didus Ineptus. The plural of Didus is Didinae; the adjective form is Didine. Say “Didus,” “Didinae,” or “Didine,” or any combination thereof three times fast, and I challenge you not to blurt out the word “dude” at some point. The name of the species even falls right in line with the original sense of the word, “Dude.”

The use of the word “Dodo” to describe a “Dude” (or Dandy or Swell) may have been new in 1882, but it was consistent with centuries-long practice of describing fashion-conscious men, like the “Dude.” Words like popinjay, peacock, cock of the walk, rooster, and other bird imagery had long been used to describe fashionable, preening men, as discussed further below.

The use of “Dodo” to describe a “Dude” also reflects the element of foolishness or uselessness, embodied by the “Dude.” Not only does the scientific name of the species (Didus Ineptus) suggest stupidity, the English word, “dodo,” has the secondary meaning, “a foolish person.” In 1883, however, that secondary sense of the word was brand new.

The Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang lists the earliest attestation of, “dodo,” in the sense of “a fool,” as 1898. The online etymology dictionary, etymonline.com, lists the earliest use of “dodo,” in the sense of “stupid persons,” as 1888. The pre-“Dude” story, Natural History, may, in fact, be the earliest known attestation of the word, “dodo,” in the sense of a stupid person. I have not seen any other source showing an earlier date of this sense of “dodo.”

Robert Sale-Hill’s poem, The History and Origin of the “Dude,” may have played on the new sense of the word “dodo” to allude to the silliness of the “Dude.” The earlier use of “dodo” to describe Dude-like characters in the story, Natural History (and the poem it inspired), suggests that the word “Dude” may even have been based, in part, on the word “dodo.”

I acknowledge that, standing alone, the suggestion that “Dude” derives from “Dodo,” might seem ridiculous; as ridiculous as a dodo, perhaps.

But several striking similarities between

The History and Origin of the “Dude,”and the story,

Natural History (and the poem that the story inspired), make it plausible, if not probable, that “Dude” owes as much to “Dodo,” as it owes to “Yankee Doodle” or to two-syllable “dude” (doody).

[x]

The History and Origin of the “Dude”

Sale-Hill’s poem, The History and Origin of the “Dude,” reads like a natural history lecture about a bird called the “dude.”

In Robert Sale-Hill’s poem, Dudes travel in “flocks” and their banged hair looks like:

. . . feathers o’er their brow.”

They have bird-like legs, feet and wings:

A pair of pipe stems, cased in green, skin-tight and half-mast high, sir. To this please add a pointed shoe . . . . You see them flitting o’er the pave, with arms – or wings – akimbo.

Dudes live in nests, eat like birds, dress like birds, and fly like birds:

They have their nests, also a club, . . . Like other birds they love light grub . . . .

They plume themselves in “foreign plumes.”

The Brush Electric Lighting Co. have cased their lights in wire for fear, attracted by the glow they’d set their wings on fire.

Dudes were vain and stupid:

Its stupid airs and vanity made the other birds explode, so they christened it in charity first cousin to the “Dodo.”

For idiocy it [(the Dude)] ranked with “lunes,” and hence surpassed the “Dodo.” . . . .

The History and Origin of the “Dude” was also published in book form.

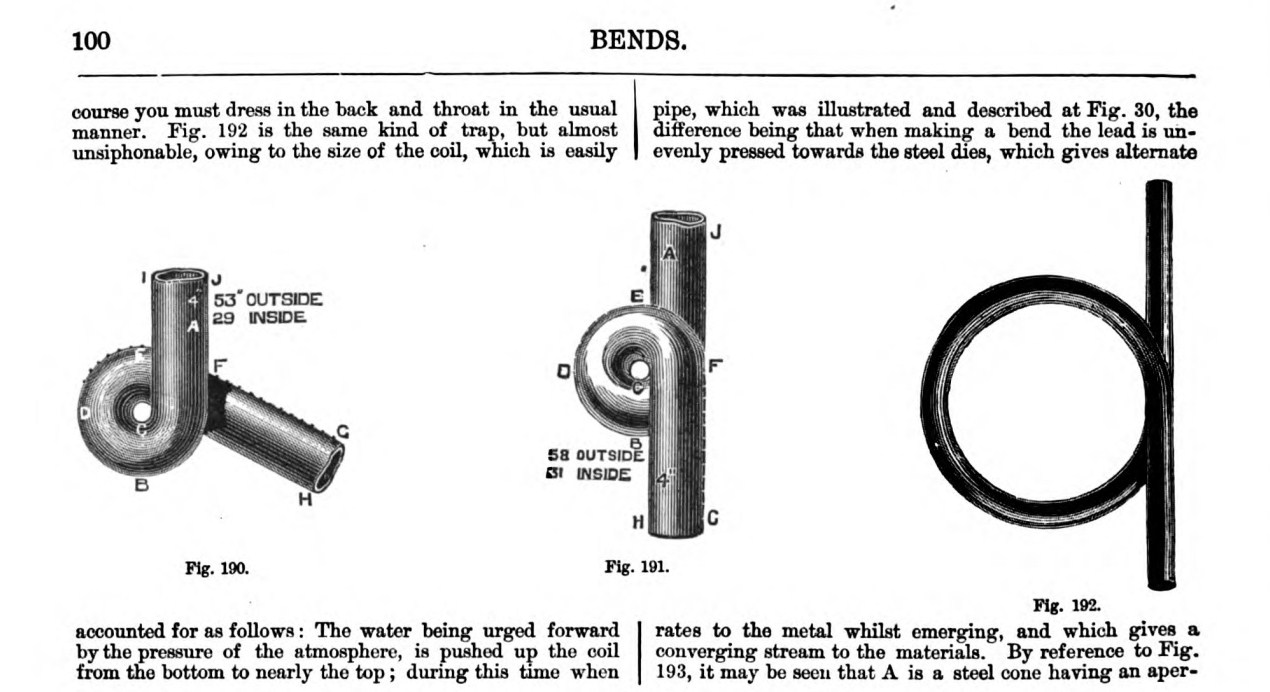

The cover illustration of the book shows a Dude descending a staircase (long before Duchamp’s

Nude Descending a Staircase), a coat-of-arms, and a book.

The coat of arms includes a shield, divided by a diagonal bar running from the lower left to the upper right; the diagonal bar decorated with dollar signs (such a bar is known as a "

Bend Sinister" (or "

Bar Sinister"); indicative of bastardry).

Above the bar is an image of a dodo, and below the bar a donkey or an ass.

A top-hat with donkey ears crowns the top of the shield.

The dude’s motto, “Much money but little brains,” is spelled out (in French) on a banner spread out beneath the shield.

![]() |

| Robert Sale-Hill (illustrated by Henry Alexander Ogden), The History & Origin of the “Dude,” New York, Rogers & Sherwood (undated - 1883?) |

Below the coat of arms, a large-format book is opened to a page displaying a full-page image of a dodo. The heading reads, “Natural History.” The caption below the image reads, “Ineptus (Lat. Stupid).” The word, ineptus, is not merely a joke, insinuating that “dudes” are inept, it also the scientific name of the species, Latin for foolish or useless.

Natural History (of the Dodo)

In August and September 1882, a poem credited to the Burlington, Iowa

Hawkeye, appeared in at least three additional newspapers or magazines, located in Washington DC, Chicago, and Vermont.

The same poem appeared again in Seattle in March, 1883:

[xi]Dodo

“What is that, mother?”

“The dodo, my child;

His thoughts are weak and his brain is mild.

‘Tis he that levels the empty gun

At his timid sister in dodo fun,

And rocks the boat on the summer lake

To hear the screaming the ladies make.

He wears lean pants and tooth-pick shoes,

And hasn’t an ounce of sense to lose.

Look at him close as you see him pass,

He looks like a man, but was made for an ass.”

– Hawkeye

The lean pants, tooth-pick shoes, and not having “an ounce of sense to lose,” all echo elements of Robert Sale-Hill’s poem. The comment that he was “made for an ass,” also echoes visual elements from the cover illustration for The History and Origin of the “Dude.” Other elements of the story that may seem kind of random (the timid sister, rocking the boat, hearing the ladies scream), are all borrowed directly from the story that inspired the poem, Natural History.

Natural History, which was credited to the

Detroit Free Press, appeared in at least five other newspapers in 1882; across a widespread geographic area, including Washington DC, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Missouri.

The same article also appeared in Kentucky, in February, 1883, and in

Donohoe’s Magazine, in 1884.

[xii]

The story reads like a natural history lecture on “Dodos,” all kinds of “Dodos,” including stupid, self-centered and inconsiderate young men who affect an English accent.

Natural History

Professor, what is a Dodo?”

“There are several species of the Dodo, my son, and there used to be several more before the fool-killer cut the country up into regular districts.”

Please describe some of them to me.”

“With pleasure. You have probably attended a Sunday-school picnic given on the banks of a lake or a river? Six fat women, two girls who wear eye-glasses, and a very good boy who lisps, make up a party to take a ride on the water. As they are ready to shove off the Dodo appears, and keeps them company.”

“What is he like, and what does he do?”

“He is generally a soft-headed young man under 23 years of age, and he stands up and rocks the boat to hear the fat woman scream and to induce the girls to call him Gweorge.”

“Does the boat upset?”

“It does.”

“And is everybody drowned?”

“Everybody except the Dodo. He always reaches the shore in safety, and he is always so sorry that it happened. He is sometimes so affected that it takes away his appetite for lunch.”

“And is anything done with him?”

“They sometimes rub his head with cheap brand of peppermint essence and turn him out to grass, but no one ever thinks of doing him harm.”

“And the next species?”

“The next species is a youth from sixteen to twenty. He labors under what the ancients termed the swell head. He gets out the family shot-gun or revolver to show off. He points it at some boy or girl to see ‘em shiver; and after he has testified before the coroner that he didn’t know it was loaded the affair is looked upon as ended.”

“Is this species on the increase?”

“Well, no. The friends of the victims have got to making such a fuss over these trifles that the didn’t-know-it-was-loaded Dodo isn’t quite holding his own.”

The rest of the article goes on to describe two kinds of female dodos; one that “accidentally” poisons her husband by mixing up rat poison with baking powder (she also “forgot” about his insurance policy); and one who, “gets into society on the strength of her false hair, small waist, painted eyebrows, chalked cheeks and cramped feet.”

Similarities between History and Origin of the “Dude” and Natural History (of the Dodo):

The similarities between “Natural History” (of the Dodo) and the “History and Origin of the ‘Dude’” begin at the beginning; in the title. They both include the word, “History,” and both are written using the conceit that this new form of person is a bird-like creature. The cover illustration for the original “Dude” poem even shows the phrase, “Natural History,” above an image of a Dodo.

The pre-1882 poem describes a “Dodo” with “lean pants and tooth-pick shoes;” Sale-Hill’s poem refers to a “Dude” with “a pair of pipe stems, cased in green, skin-tight and half-mast high” and “a pointed shoe.”

The earlier poem,

Dodo, notes that “Dodos” are “made for asses;” the cover illustration for the later “Dude” poem prominently pairs images of a dodo and an ass on the coat of arms.

The “Dude” is said to follow English fashions, and the “Dodo” wants the girls to call him, “Gweorge,”

[xiii]in the style of an English accent.

Although the English accent, as such, is not spelled out explicitly in Sale-Hill’s “Dude” poem, dozens of dude-craze articles describe dudes as speaking with affected, English accents.

Other Pre-Dude Dodo References

An interesting aspect of this story is that it may be the earliest known example of using the word, “dodo,” to mean a stupid person. Previously, when “dodo” was used disparagingly, it had generally referred to something being outmoded, having outlived its usefulness, or being extinct. Since the secondary meaning of “dodo,” in the sense of “a stupid person” is not known to have existed before 1882, it is possible that “Dodo” and “Dude” may have entered the lexicon, hand in glove, at nearly the same time.

In November 1882, a humorous story about a heart-sick young man also used the word “dodo,” in the sense of a stupid person, but not in conjunction with a clearly, dude-like character.

The story, credited to the

Detroit Free Press, appeared in the Nebraska and Missouri in late 1882.

[xiv] It also appeared in several newspapers, in other parts of the county,

[xv]in the days and weeks following publication of the original “Dude” poem, but before dude-mania had taken off:

A Doctor’s Substitute

He was a young man with a wild, disordered look. He rushed into the office of a prominent city physician yesterday, placed a small cup on the desk, took off his coat and bared his right arm and whispered; “Stick me!”

“Do you want to be bled?”

“I do! Open a vein and let me catch the blood in this cup.”

Too full in the head?”

“Alas! Too full in the heart. My affianced will not believe me when I tell her that I lover her better than my life. I will write my love – I will write it in my own life-blood! Proceed!”

“Is that all you want?”

“All? Is not that sufficient?”

“Young man, you are a dodo! Put on your coat! I keep a red ink here for the very purpose you desire, and I will sell you a whole gill for a quarter!” And the young man was not stuck.

Omaha Daily Bee, November 23, 1882, page 3, column 3; The County Paper(Oregon, Missouri), December 15, 1882, page 7, column 2; News and Herald (Winnsboro, South Carolina), January 18, 1883, page 1; Millheim Journal (Pennsylvania), February 1, 1883, page 1; Columbus Journal (Nebraska), February 14, 1883, page 4..

A viral joke that made the rounds, starting in late-November 1882, also demonstrates that the word, “dodo,” had become a known insult, although the meaning of the insult is not clearly illustrated by the joke:

“No, I didn’t mind being called a mastodon and a dodo,” said an Illinois judge; “but when that female said I was ‘a two-legged relic of a remote barbaric period,’ I was compelled to fine her for contempt of court.”

The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, November 28, 1882, page 3, column 4 (The same joke appears in numerous other sources in December 1882. The comment purportedly stemmed from a divorce proceeding in Chicago.).

Post-Dude Dodo References

Robert Sale-Hill’s poem, The History and Origin of the “Dude,” comparison of a “Dude” to a “Dodo” may have worked on two levels. It conveyed the idea of foolishness or stupidity, consistent with the Latin name of the dodo’s species, Ineptus, and with the relatively new, secondary meaning of “dodo,” in the sense of “a foolish person.” In addition, the use of bird-imagery to describe dandies, fops and swells was centuries old.

In first months of the “Dude” craze, following publication of Robert Sale-Hill’s poem, The History and Origin of the “Dude,” many writers latched on to both senses of the dodo metaphor. Numerous stories, poems, and jokes extended the natural history-lesson motif of the original poem, to even more ridiculous lengths. Although writers could have been responding to the “Dude” as “Dodo” metaphor in the original “Dude” poem, the fact that the word “dodo” had already been associated with tight pants-wearing, toothpick shoe-wearing, stupid young men, before 1883 suggests that the “Dude” as “Dodo” metaphor succeeded because of a general awareness of the new sense of the word “dodo,” and an understanding of the dandy-as-bird metaphor.

A humorous story, from Boston, illustrates the use of the word, “dodo,” in the sense of “a stupid person,” to insult a “dude”:

Labeling a Boston Dude.

From the Boston Journal.

A prominent member of the band of gilded youths of which this city is so justly proud is in a high state of excitement, and with difficulty held back by his friends from making a personal assault upon his jeweler, who, he conceives, had been “putting up a joke” on him.

The facts, as gained during his lucid intervals, are these: - He is much addicted to attending the dramatic performances which occur in this city, his specialty being in steadily observing the female chorus in comic opera, and the sylphs of the corps de ballet in their ingenious gyrations. It struck him that it would be a good notion to wear a scarf pin suggestive of his love for the lyric stage, and accordingly interviewed his jeweler upon this momentous subject. The artificer in precious metals was prompt to meet the demands of the occasion, and in due time presented his customer with a neat design, consisting of a bar of music delicately fashioned in gold, with the treble clef in black enamel, and two notes in diamonds reposing between the third and fourth lines from the bottom.

The customer, whose only knowledge of music was as it suggested the accompanying incident of female singers, highly approved this work of art, purchased it, stuck it in his scarf and went down to the matinee. After the performance he displayed his new possession to the ladies, who admired it much. At last he showed it to the prettiest and brightest one of all, who immediately exclaimed, “How very neat and appropriate!”

“Do you think so?” inquired the delightful youth.

“Certainly I do, and those beautiful diamond notes; they fit you so well. Do, do – that makes dodo, you see. How ingenious and how very true!” – and she tripped away, amid the loud laughter of all the assembly. And, although the jeweler swears by the golden calf that he is quite innocent in the matter, he has thus far failed to make his customer believe it.

Evening Star (Washington DC), April 25, 1883, page 3, column 3.

Dude/Dodo references abounded during the early post-dude poem era. Many of the references follow the natural history-lesson motif, treating the dude as though it is a rare species of bird, which is as dumb as a dodo, or descended from the dodo, or too stupid to have descended from a dodo. Many of the stories play off the actual scientific name for the dodo, Didus Ineptus, or a made-up scientific name for dude, Dudus Americanus.

In one of the earliest references I’ve seen, from outside the New York Metropolitan area, the word “dude” is misspelled as “dudu” – whether by design or by accident, the word was just on the cusp of attaining wide celebrity, and may have been unfamiliar to the editor or typesetter. Another newspaper printed the same article with the correct spelling a couple weeks later:

The term “dudu” is now applied to those dandified young society chaps in New York who are “just too nice for anything.” The word is changed from dodo, an extinct member of the duck species, the peculiarity of which was its ridiculously small wings and tail on a big, puffed-up body.

The Rock Island Argus (Illinois), February 28, 1883, page 2; Burlington Weekly Free Press (Vermont), March 9, 1883, page 3 (spelled “dude”).

The reference to “small wings” echoes the line, “arms – or wings – akimbo,” in the original “Dude” poem. The reference to a “tail” may refer to the “dude” fashion of wearing long tails under a short overcoat.

On March 17, 1883, an article appeared in the Washington National Republican, about a reported sighting of a rare, fox-like quadruped previously believed to have been extinct. The headline of the article was, “The Missing Companion of the Dodo.” Two days later, a brief humor piece appeared in the same paper, playing off that headline:

Somebody wants to know what is the missing companion of the dodo. The dude, of course.

National Republican (Washington DC), March 19, 1883, page 4, column 1.

Harper’s Weekly published a cartoon showing the dudes as ostriches in the zoo – not dodos, but birds, nonetheless. The caption reads, “The New Bird. Ornithology. Dodo, Dudo, Dudu, Didi, Dou Do, a bird of the genus Didus. Didus, a genus of birds including the Dude”:

Harper’s Weekly, March 31, 1883, volume 27, page 208.

Life magazine published a cartoon showing three grammatical variations: Present. Do or Du. Remnant of the Dodo. / Past. Dun. The result of an over done, dreary existence. / Perfect. Dude. A parasite from Yankee-dude-l:

Life, Volume 1, Number 19, May 10, 1883, page 221 (note the coattails sticking out from under the “Present” Dude’s overcoat).

The Washington Critic published a series of “dude” articles that pushed the dude-as-bird metaphor:

“Well, I think we will have a rather late spring. You see there is a new kind of bird which has come into our section of country, a very rare bird. I don’t know what the bird is good for, nor do I know where it came from. I don’t think they are fit for anything, though I see quite a number of them here in Washington. The majority of them here and all in our section are young birds, though I see some old ones here. I saw an old one at the theatre last night.”

“Which theatre?”

“Ford’s. He occupied a front seat, and seemed to take a great deal of interest in the crowd. He had a very large pair of opera-glasses, and was continually bouncing up and down looking at the vast assemblage of people in the theatre.”

Now, the Critic would like for you to explain what use a bird has for opera-glasses.”

Lord bless your soul, this bird that I have been talking about is a dude, and I tell you they are getting to be a little too numerous in this section for the good of society. They are a little too fresh. We must do something to get them out of the country or they will ruin it.”

Evening Critic (Washington DC), April 17 1883, page 2.

Apparently unsatisfied with the term “dude” from New York, a writer in Washington DC tried coining an alternative expression; the “Phil-a-lu-bird.” Once again, the story involved an expensive (I suppose) pair of opera glasses:

“The phil-a-lu-bird is another species of bird that has made its appearance in our city,” said an old citizen withint the hearing fo the Critic last evening.

“The phil-a-lu-bird is another species of bird that has made its appearance in our city,” said an old citizen within the hearing of the critic last evening.

“Phil-a-lu-bird! Now, what kind of an animal is that?”

“Well, he is a slight improvement on the dude. He is possessed of all the attributes of the dude, and has an additional qualification. He wears sharp-toed shoes, Derby hat, tight pants, shad-belly coat, striped cravat, a red handkerchief in his pocket, the corner sticking out, smokes cigarettes, wears bangs and whistles through his nose, so as to be heard for miles around. Oh! He is a bird. I tell you, he is a dandy. I saw one at the theatre last night with a $1 pair of opera-glasses. He was occupying a twenty-five cent seat. You can see the phil-a-lu-bird on the street at all hours of the day. He is more dangerous than the dude in many respects.”

The Evening Critic (Washington DC), April 24, 1883.

The same newspaper again referred to the “phil-a-lu” bird in a poem about a dude:

The dude, the dude,

Belongs to a brood

Of birds like the phil-a-lu;

He struts the street,

With picket-toes feet,

And slings a cheap bamboo.

The dude, the dude,

Is always rude

With his idiotic star;

He poses for the girls,

With his bangs and curls,

Trying to “mash” everywhere.

The dude, the dude,

With manners crude

And cheek of the rarest kind,

Essays to talk

Where angels balk

And inflict his silly mind.

The dude, the dude

Is not indued

With the fact that he’s an ass;

Every one knows

Him by his clothes

As on the street he’s seen to pass.

Evening Critic (Washington DC), April 26, 1883, page2.

I have been unable to determine whether “Phil-a-lu” has any particular significance. It sounds like a reference to Philadelphia, perhaps. But I have also found two references suggesting that it may be a word from Irish mythology. In both cases, however, it seems to be used more in the nature of an interjection, than a noun. Although in one case, it is spoken by a strange, almost bird-like beast.

In the poem, Derevaragh, A Legend of the Great Lake Serpent, the “beast” cries, “Philalu!” at Saint Patrick. The beast looks like a cross between a snake and a bird, with a snake’s body and tail, small bird’s feet, and small wings (or fins?) near its head:

‘Philalu!’ cried the beast, ‘and chone! Philalu!

Saint Patrick, my darling, don’t look so blue.

London Society, Volume 24, September, 1873, page 251.

Philalu also appears in another Irish poem:

Ochone an’ ullagone ! we must vainly sigh an’ groan’’

Philalu! A long adieu to Clifford Lloyd!

Caoine of the Clare Constabulary, from Arthur M. Forrester, An Irish Crazy-Quilt, Boston, 1891, page 77.

An article that was printed at least in New York City, and Washington DC, further developed the natural-history-of-the-dodo motif:

The Dudus Americanus.

The Dudus Americanus, or American dude has of late been the subject of much scientific inquiry. Yet little light has been thrown upon his origin and development. . . .

It is held by many that the dude is the descendant, through a long course of evolution, of the dodo, because of the similarity in name and because the dodo strutted about as though it were pleasing to look upon, whereas it was ridiculous in appearance. Moreover, the dodo is described as “stupid and incompetent.”

These points certainly favor this theory, but one objection has been overlooked. The dodo was strong, and was feared by numbers of smaller species. No one, however, fears a dude. He lacks the wit and physique to harm by word or act. Consequently, the claim that he is a descendant of the dodo is contrary to the theory of the survival of the fittest.

Again, those who maintain that the Dudus Americanus is not a separate species, but a deterioration of the Dudus Britannicus, point to the fact that while the American dude may be the offspring of American parents, he receives the finishing touches from an English tailor. Moreover the American and the British dude have much in common. Both are reserved in conversation not from choice, malicious people say, but from necessity. Both are rather attenuated in figure, a peculiarity attributed to the fact that their only nutriment appears to be the small quantity of alimentary matter derived from sucking the silver heads of their canes. Both are proud of their families, though their families were never known to be proud of them.

But there is a common sense view of this question which yields more satisfactory results than scientific research. In all ages that class of people in society who have been too stupid to discover their ignorance have been held up to ridicule and contempt. Names have been invented for them which would properly reflect the opinion of the sensible portion of the community concerning them. “Dude” is simply the latest of these names.

The Sun (New York), April 27, 1883, page 2, column 3; Evening Critic (Washington DC), May 2, 1883, page 1, column 6.

The expression “Dudus Americanus” survived for a time, at least on a small scale; it popped up in print at least two more times during the next few years. St. Paul Daily Globe, April 25, 1884, Page 3; The Austin Weekly Statesman(Texas), May 03, 1888, Page 6.

A Dude is a Bird

A poem published in 1881 refers to “dandies” as rara avis(latin for “rare bird”), much in the way that the dodo story and poem in 1882 used the word “dodo.” Although, admittedly, a rara avis is not necessarily stupid or inept like a dodo (didus ineptus), it is at least consistent with the long-standing practice of using bird imagery to describe dandies. Calling them “dodos” – to incorporate the idea of their being stupid – was the special genius of whoever wrote the “Natural History (of the Dodo)” – and coining the simple, memorable word reminiscent of dumb dodos – “dude” – was the special genius of Robert Sale-Hill, if, in fact, he coined the word on his own for the poem.

The same poem uses the word, “fopdoodle,” which shows that the word, though already considered archaic, was not completely dead in the early 1880s. I discuss the possible influence of “fopdoodle,” and its derivatives, on the origin of “Dude” further, below.

Poem, The Dandy.

The Dandy – pshaw! The funky mess –

Conceited, powdered noodle,

With naught of value but his dress, -

A noddy, a fopdoodle.

This rara avis strutting goes

On end like human creatures;

That vacant shell behind the nose

Is shaped like human features.

[Tis bootless task to hunt for soul,

No matter what our craving,

Nought can we do but save the hole,

And that’s not worth the saving.]

His locks done up with curling rods,

His bosom gemmed with broaches,

Whate’er of him would please the gods

Is shamed by the cockroaches.

Trinkets adorn his paws and ears

In fashion most exquisite;

“Poll”* sees! – abashed and most in tears,

At first cried out: “What is it?” –

Then, “Hell of cheat! Carcass and curls

And every merit counted,

Fit walking-stick for silly girls,

Brass-headed and gold-mounted!”

Sooner than that waste thing, a fop,

I’d be a clam or donkey,

Or hooting owl on yon tree top,

Or weathercock or monkey.

J. Fletcher Hollister, Sunflower; or, Poems, Plano, Illinois, 1881.

Although the “dandy” of the poem is not the precisely the same “type” as the “Dude,” the means of ridicule are similar. The dandy is a rara avis– a bird. He is vain – with a “powdered noodle,” which I take to mean a powdered wig on his head. As in the The History and Origin of the “Dude,” he carries a cane, and is unflatteringly compared to a donkey and a monkey.

Rara avis was also used occasionally in association with the word, “dude,” suggesting, perhaps, a residual understanding of “dude” as a metaphorical form of a bird:

While a party of visitors to the wrestler were sitting on the porch, a hack drove up containing ex-Governor Perkins, Bishop Kip, and two just arrived English tourists of distinction, one of whom was a dude of the most pronounced and unmistakable type.

As soon as this rara avis descended from his carriage for refreshments, Senator McCarthy at once concocted a fell scheme, into which he initiated the other bold bad men at his side.

The Abbeville Press and Banner(Abbeville, South Carolina), July 25, 1883, page 4.

“Papa,” said Willie, “what is a rara avis?”

“A rara avis, my son, is a dude with brains. You hardly ever see one.” – New York Sun.

The Comet (Johnson City, Tennessee), August 7, 1890, page 1.

Bird Imagery in Speaking of Dandies

The use of bird imagery to describe men in fancy clothes goes back centuries, if not millennia. Aesop’s fables about the jay and the peacock, tells of a lowly jay who tied peacock feathers to his tail to impress the peacocks. They were not impressed, and pecked at his tail and removed his feathers. When the jay went back to his own kind, they were annoyed with him too. The moral of the story: “It is not only fine feathers that make fine birds.”

Terms like “popinjay” (a “

a strutting supercilious person,” from the Middle English

papajay(parrot))

[xvi], peacock, cock of the walk, and rooster, often used to describe fashionable, strutting, preening men, illustrate the long-standing practice of using bird imagery to describe fashion-conscious men.

Bird imagery was still in regular use in the years prior to the coining of the word “Dude.”

A few examples from the period illustrate the practice:

The True Man and a Dandy.

Birds of gaudy plumage attract the eve, whether perched on tree or found in parlor; their feathers alone are valuable. So it is with the dandy. His fashionable attire; his hair parted in the middle and covered with odiferous cosmetics; his whiskers (if he has any) require his constant care; his effeminary); his general appearance – summon our attention as we survey him. Whether on the streets, armed with a gold (brass) headed cane, or in company, with soft hands protected in gloves, we find him full of pride, full of conceit, full of nonsense and prattle. He admires his superior dimensions, and imagines himself a master of arts, of literature – a very fountain of wisdom. Deceit, flattery and extravagance, however, are his prominent characteristics. Of no material use to himself or to others, he believes he is a superior being. It is true, he is too good to work, but not too good to fritter his time in idleness and pleasures; too goo to earn a livelihood, but not too good to live off the earnings and skill of others. He is too pre-occupied with his great understandings and pompous nothings to notice others, fortunately, not affected with “softening of the brain,” and returns to the earth from whence he came, and which he treads with such haughty mien unregretted – soon forgotten and replaced by other birds of the same feather.

Rocky Mountain Husbandman(Diamond City, Montana), March 20, 1879, page 5, column 2 (credited to Cor. Rural World).

“Peacock Finery.”

When “Pitman George” had become “Old George” to his friends, and “Mr. George Stephenson,” the great railroad engineer, to the public, he was noted for his plainness in dress.

Though often in contact with lords and dukes, he fastened his white necktie with a large brass pin, and wore no ornament – watch-chain, breast-pin, or ring.

Mr. Stephenson hated foppery in young men – “peacock finery,” he called it – as one youth learned to his sorrow.

He was “old George’s” private secretary, and loved to dress in a showy style, though, when in the old man’s presence, he restrained his propensity. But one unlucky day, intending to take a stroll, with two “swell” friends, through the fashionable quarter of London, he dressed himself as a dandy.

His costume was patent-leather boots, light-colored trousers, and a tightly-buttoned coat of blue cloth, within which was seen a line of a white vest, with a pink shade under it; white wrist-bands turned back six inches over the coat-sleeves, a black satin scarf from which glistened two diamond breast-pins, connected by a delicate gold chain, light gloves, and a shiny silk hat and a small cane.

As he was sauntering through the street, filled with promenaders, who should he meet but “old George.” The two friends left, but Mr. Stephenson, taking his secretary by the button, turned him round and round, as if showing him off to the passers-by.

A crowd collected. At last, releasing the youth, “old George” blurted out, in his strongest Northumbrian accent, -

“Young man, you have lived five years at my house, but I never knew I was harboring an American jackadaw.” [(A jackdaw is a crow-like bird.)]

What an “American jackadaw” was, the youth knew not, save that it was something indicative of contempt. Of course, he was mad; but as his employer never referred to the “sight,” he was wise enough to remain silent. It worked, however, a change in his “peacock finery.”

The Youth’s Companion, Volume 52, Number 48, November 27, 1879, page 417 (reprinted in Bismark Tribune (North Dakota), May 14, 1880, page 6 Column 2.

A story about anthropomorphic roosters and chickens reversed the usual metaphor, describing fine-feathered birds as dandies:

Presently young “Dandy Bantam” appeared upon the scene, gorgeous in his coat of many colors, with a bright orange vest, and high top boots with spurs.

He turned his head with its scarlet crest from one side to the other, trying his best to look as tall as Sir Doodle Shanghai [(Shanghai rooster, a type of rooster)], but his lordship snubbed him so pitilessly that he slunk away quite mortified, though his spirits rose again at sight of his pretty cousins. . . .

Having presented in the same way a sweet petal to each of his followers, he fluffed up his feathers, tossed back his head, lifted up one foot, and shouted, “Cock-a-doodle-doo-oo-oo!”

The Youth’s Companion, Volume 52, Number 31 (Boston, Massachusetts), July 31, 1879, page 259.

Although a dodo is a silly bird (ineptus,is its last name, after all), the word does not appear to have taken on the secondary meaning of a foolish or stupid person until 1882. And, as a silly bird, it was not generally one of the birds mentioned when bird-like imagery was used to refer to dandies; peacocks, roosters, and other pretty birds were more frequent targets. Nevertheless, the story, Natural History, was not the first time that the word “Dodo” was used in association with a dude-like character or dandy. William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel, The History of Pendennis briefly refers to a young swell named, “Lord Viscount Dodo,” as well as another young swell whose name, “Popjoy,” evokes the dandyish word, “popinjay”:

“You know, as well as anybody, that the men of fashion want to be paid.”

“That they do, Mr. Warrington, sir,” said the publisher.

“I tell you he’s a star; he’ll make a name, sir. He’s a new man, sir.”

“They’ve said that of so many of those young swells, Mr. Warrington,” the publisher interposed, with a sigh. “There was Lord Viscount Dodo, now; I gave his Lordship a good bit of money for his poems, and only sold eighty copies. Mr. Popjoy’s Hadgincourt, sir, fell dead.”

The History of Pendennis, Volume 1, Boston, Estes and Lauriat, 1882, page 322 (originally published between 1849; regularly in print thereafter).

Coincidentally, perhaps, William Makepeace Thackeray, also penned, “The Fitz-Boodle Papers,” and is known to have written under the name, “George Fitzdoodle,” which appears to be derived from “fopdoodle.”

A Dude is a Fopdoodle

In his book, The Story of English in 100 Words, David Crystal describes the origins of the word, “fopdoodle” (or “fop-doodle”):

People started to use the word fopdoodlein the 17th century. It was a combination of fop and doodle, two words very similar in meaning. A fop was a fool. A doodlewas a simpleton. So a fopdoodle was a fool twice over. Country bumpkins would be called fopdoodles. But so could the fashionable set, because fophad also developed the meaning of 'vain dandy'. Dr Johnson didn't like them at all. In his Dictionary he defines fopdoodle as 'a fool, an insignificant wretch'.

Fopdoodle is one of those words that people regret are lost when they hear about them.

If people regret the loss of the word, “fopdoodle,” perhaps we can rejoice in the possibility that the word is still with us, at least in part, as the word, “Dude.”

If Robert Sale-Hill coined the word, in part, from the word “Dodo,” in the tradition of bird-imagery to describe dandies, perhaps the word, “fopdoodle,” or one or the other “doodle” words that were in vogue at the time, influenced his decision to rearrange the letters to spell “dood” or “dude.” “Dodo,” after all, had already been used to mock dude-like characters in the story, Natural History, and the poem that it inspired. But that usage did not stick, or at least not to the same degree that “dude” did after its debut. The secondary meaning of “dodo,” meaning a foolish or stupid person, may have survived independently, but the more specific meaning of “Dude” struck a particular chord with the public. Perhaps it resonated with the word, “fopdoodle,” and/or its offspring, “Fitzdoodle” and “Fitznoodle,” which were both in regular use to describe dandies in the years leading up to 1883, and continuing afterward.

Charles Dunphie used the word “fopdoodle” in his essay on, Fops and Foppery, in 1878. The word “fopdoodle” also appeared in the poem, The Dandy, in 1881. In 1890, a correspondent of Notes and Queries considered “fopdoodle” a plausible influence on the origin of “dude.” Although the word was already considered archaic by the 1880s, it still appeared in print with some regularity, even beyond the references already cited.

In 1888, for example, a brief newspaper item mentioned that:

In early English times dandies were known as “fop doodles.”

Orleans Monitor (Barton, Vermont), January 30, 1888, page 4, column 2.

In his essay on Fops and Foppery, Dunphie notes:

In Hudibras we find mention of a creature known as a “fopdoodle.” “You have been roaming,” says Butler,

“Where sturdy butchers broker your noddle,

And handled you like a fopdoodle.”

The “fopdoodle” now exists only in the dictionary. It is no great loss, for his name was sufficiently expressive of his silliness.

Charles Dunphie, The Splendid Advantages of Being a Woman, page 72.

The book, Hudibras, is, or was, considered a classic early 17th century piece of satire. During the mid-1800s, new editions of the book still came out two to four times each decade. The book was apparently very well known and had been read by many people.

The word also appeared in American writing:

I, on the contrary, chimed in with the varlet’s frolicsomeness, and, giving loose to my risibility, laughed, as long and as loud, as any fop-doodle, at his first-born pun!!!

Costard Sly, Sayings and Doings at the Tremont House in the Year 1832 Volume 2, Boston, Allen and Ticknor, 1833, page 183.

The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge reportedly included the word “fop-doodle” in a list of insults, when favorably comparing the English language’s broad range of insults with those available in Greek:

We are not behindhand in English. Fancy my calling you, upon a fitting occasion, – Fool, sot, silly simpleton, dunce, blockhead, jolterhead, clumsy-pate, dullard, ninny, nincompoop, lackwit, numpskull, ass, owl, loggerhead, coxcomb, monkey, shallow-brain, addle-head, tony, zany, fop, fop-doodle; a maggot-pated, hare-brained, muddle-pated, muddle-headed, Jackanapes! Why I could go on for a minute more.

Henry Nelson Coleridge, Specimens of the Table Talk of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 2d Edition, London, J. Murray, 1836.

Thirty years later, Edward Vaughan Kenealy, extended a similar list of insults to nearly four pages of dialogue:

Shatter-pate, Swinge-buckler, Boggler, Chatterpie, Bamboozler, Dodger, Meacock, Buzzer, poor Fopdoodle, You’re a pretty first floor lodger!

Edward Vaughan Kenealy, A New Pantomime, London, Reeves and Turner, 1865, page 395.

Similar lists of insults in Gentleman’s Magazine in 1875 and 1876. Kenealy’s piece, including the word, “Fopdoodle,” was cited on occasion; and his, A New Pantomime, was included in a collection of his poetical works published in 1878.

Fopdoodles were a concern long before “Dudes” made people cringe:

Have We a Jenkens Among Us?

Editor of the Argus: - Sir: Is it possible that we have a real Jenkens among us? Are we about to enter a career of great snobbery? Is the style of ladies’ dresses more important than what is in their heads? Are the fop doodles who carry their fans the leaders of society? I should think so, from a recent snobbish editorial in the Union.

Common Sense.

The Evening Argus (Rock Island, Illinois), September 24, 1867, page 3, column 1.

Last Name Fopdoodle

The word, “fopdoodle,” was used on occasion as the last name of a dandy-like character:

Lord Fopdoodle or a Sir Dilberry Diddle, who has hurried to be in time at a grand dinner-party of Corinthians. . . .

“What taste!” cries Lord Fopdoodle; “c’est unique!”

“Par Dieu!” exclaims Lord Froth, ‘c’est magnifique!”

The Yahoo; a Satirical Rhapsody, New York, H. Simpson, 1833, pages iiiv and 77 (reprinted in 1846 and 1855).

The play,

The Merchant Prince of Cornville, first produced in London in 1896, has a character named Fopdoodle, a “fop, suitor of Violet.”

[xvii]

Two names apparently derived from “fopdoodle” frequently appear in comedic or satiric writings; often as the last name of a dandy, Englishman, or wealthy businessman; in short, the types of people who might have been called “dudes” in 1883.

Last Name Fitzdoodle

Characters named “Lord Fitzdoodle” (very similar to Lord Fopdoodle) appear in several books and plays written and published in both the United States and England, from as early as 1859 and as late as 1909. William Makepeace Thackeray, who died in 1863, is said to have sometimes written under the pen-name, “George Fitzdoodle.” Various characters named, for example, “Mr. Fitzdoodle,” “Reverend Fitzdoodle,” “Major Fitzdoodle,” “Young Fitzdoodle,” and “Fred Fitzdoodle” appeared in print between 1858 and 1874.

In 1880, a Sacramento newspaper complained about rampant graffiti and vandalism at the California State Capitol building; the “Fitzdoodles” were to blame:

The walls of several of the corridors, passageways and the exterior walls of the dome have been very badly marked up and disfigured by chalk pencil and charcoal, and a whole library of directories could be compiled from the records made by the toots, Snips, Fitzdoodles, Noodles, Nincompoops who have attained fame by emblazoning their names in every conceivable style of chirography upon the walls.

Sacramento Daily Record-Union, May 14, 1880, page 4, column 1.

Last Name Fitznoodle

“Fitznoodle” was an even more popular, fictional last name for dandies, Englishmen, or wealthy businessmen. The name was used as early as 1838:

To Lord Fitznoodle’s eldest son, a youth renown’d for waistcoats smart I now have given (excuse the pun) a vested interest in my heart.

The name was used in association with nearly all of the attributes of a “Dude.”

Fitznoodle could be a wealthy businessmen:

“An actress!” cried Miss S. in astonishment; “oh, that is so funny; why no, she is Fitznoodle, the rich banker’s daughter . . . .”

Raftsman’s Journal(Clearfield, Pennsylvania), January 20k, 1858, page 1, column 2.

In 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, Fitznoodle was a “beau”:

They talked of war, and of the coming Fair,

How Mr. Fitznoodle was sure to be there.

(I mean at the Fair, for you’d never suppose

That war is the place for those finified beaux;

They know ‘tis a thing exceedingly rash,

Where any stray shot might spoil a mustache!

So they choose discretion preferring to stay,

To guard the dear women, as timid as they!)

Western Reserve Chronicle(Warren, Ohio), September 18, 1861, page 2.

In 1877, Fitz Noodle was a “Dandy” and a fop; and sucked on the tip of his cane:

[S]he ushered into the parlor a highly-perfumed, daintily-dressed fop.

‘Ah, my dear,’ said he, drawing off his light lavender kids, ‘please tell your mistress that Augustus Fitz Noodle awaits the pleasure of her company.’

Susan departed on her errand, and the fascinating Augustus gracefully sank in a soft easy-chair, and surrendered himself to the delightful occupation of sucking the gold head of his cane, and ruminating aloud:

‘Pleasant quarters these, by Jove!’ murmered the dandy.

The Democratic Press, February 22, 1877, page 1, column 4.

Fitznoodles were not very smart:

The subject for conversation at an evening entertainment was the intelligence of animals, particularly dogs. Says Smith: “There are dogs that have more sense than their masters.” “Just so,” responded young Fitznoodle, “Iv’e that kind of a dog myself.”

Alpena Weekly Argus, December 3, 1879, page 1 (the same joke was repeated in numerous newspapers over the next couple of years).

Fitznoodle was an Englishman:

By-the-by, what wouldn’t our fashionable mothers and worn-out chaperones give for a shrafting to be held once a year in Hyde Park? How much trouble and expense it would save; and what glorious fun it would be to see the Countess of D---- and old Lady Mantower having a hand-to-hand fight over the persons of Lord Fitznoodle or the Hon. Emilla!

The Eaton Democrat (Eaton, Ohio), April 12, 1877, page 1, column 5,

Fitznoodle might affect an English accent, or at least be pursued by a woman affecting an English accent:

One young lady at the Ocean House [(hotel in Monmouth Beach, New Jersey)] who calls butter “buttaw,” waiter, “waitaw,” wears nine diamond rings on one hand, and a bustle on which she, last night, unconsciously carried Charles Augustus Fitznoodle’s blue-ribboned straw hat from the lawn to the bluff. [Long Branch letter.

The Daily Phoenix, September 17, 1872, page 4, column 1.

After 1883, Fitznoodle could be an actual “Dude”:

First Dude – “Aw, Chawley, my dear boy, what a wattlin’ pace you are goin’ this mornin’.” Second Dude – “Aw, yes, Fitznoodle, my dear fellow. Don’t detwain me. I’m hard at work. This is the busiest season of the year to me.” “By Jove, Chawley, what are you doin’?” “I’m dodgin’ my creditors.” – Philadelphia Call.

Springfield Globe-Republic, March 6, 1885, page 3, column 3.

In the years immediately preceding and following 1883, the best-known “Fitznoodle” may have been the character from

Puckmagazine’s weekly column,

Fitznoodle in America;

a series of supposed letters to England about American society; written in a phonetic, exaggerated English accent like a “Dude.”

[xviii] Although Fitznoodle was purportedly English, not American, and was married, and probably older than the standard “Dude,” he nevertheless displayed the English style, habits, and speech associated with “Dudes,” and other silly, English, or wannabe English, dandies.

Puck, Volume 11, Number 277, June 28, 1882, page 266.

Doodle

The word “Doodle,” meaning a foolish person, existed before the word “Fopdoodle.” It was still listed in a slang dictionary in 1811:

Doodle. A silly fellow, or noodle: see Noodle. Also a child’s penis. Doodle doo, or Cock a doodle doo; a childish appellation for a cock [(rooster)], in imitation of its note when crowing.

Francis Grose and Hewson Clarke, Lexicon Balatronicum. A Dictionary of Buckish Slang, University Wit, and Pickpocket Eloquence, London, C. Chappel, 1811.

Like “Fopdoodle” and “Fitzdoodle,” the word “Doodle,” alone, also had a history of being used as a silly name.

The characters “Doodle Sam” and “Doodle Tim” were characters in

A Yankee Eclogue in 1813;

[xix]“Lord Diddle Doodle” was the name of a musical nobleman in 1775;

[xx]and “Squire Noodle and his man Doodle” were characters in the “Tragi-Comi-Farcical Ballad Opera,”

The Generous Free-Mason: or, the Constant Lady in 1730.

[xxi]

Flapdoodle (or Flap-Doodle)

In 1883, the word “Flapdoodle” (or “Flap-Doodle”) was regularly used to refer to something that was nonsensical. In 1889, a dictionary of Americanisms

[xxii]said that, “[t]o talk

flap-doodle is to talk boastingly; to utter nonsense.”

Flapdoodle and the less-common Flamdoodle are similar in form and function to “Fopdoodle,” “Fitzdoodle” and “Fitznoodle.”

The word dates to at least the 1840s and was still in regular use in the 1920s. The word was in use in the early 1880s, during the period of time immediately preceding the first appearance of the word, “Dude.” On occasion, the word was used to criticize extravagant spending, English manners and traditions, and Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement; although the word does not seem to have been necessarily restricted to that sort of nonsense:

A great deal that Oscar Wilde says is undoubtedly flapdoodle . . . . They say that he owes his present notoriety wholly to the flapdoodle, the sentimental gush, and the extravagances of language, dress and conduct that have made him and the sappy school of aesthetics whom he leads the butts of the satirist and the comic artist. The apostle of aestheticism seems to have come to America on anything but an “aesthetic” mission. – [Chicago Times Letter.

Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee), January 19, 1882, page 3, column 4.

Senator Jackson gave a thousand dollar champagne supper in Nashville the other night. Gentle reader, dost know that the grave senator is one of the four-mile flapdoodlers?

The Pulaski Citizen(Pulaski, Tennessee), August 17, 1882, page 2, column 6.

London’s Lord Mayor. Cor. Chicago News.

The incumbent wears ridiculous robes and a three cornered hat when going on anything of a formal errand. He rides in a yellow and black carriage, hung with funny curtains and ornamented by a coachman in front in a wig and blazing livery, and two footmen standing up behind, in powdered hair, knee-breeches, cocked-hats and other flap doodle decorations. These are some of the arrangements by which Englishmen are enabled to remember their grand-daddies. It will be a big day for this country when it gets over all the pomp and ceremony and other nonsense involved in its present system of government.

Cheyenne Transporter(Cheyenne, Wyoming), January 11, 1883, page 2, column 2.

Hearst’s Organ Talks Nonsense.

George Hearst’s private organ, which calls itself the Examiner, has the following piece of flapdoodle:

Sacramento Daily Record-Union(California), January 13, 1883, page 4, column 4.

Conclusion

The word “Dude” was likely coined for Robert Sale-Hill’s poem, The History and Origin of the “Dude,”which first appeared on January 14, 1883. The coining of the word, “Dude,” may have drawn from several influences, and resonated on many levels. The “Dude” as “Dodo” device was consistent with, and possibly borrowed from, the story Natural History (and poem inspired by the story) published in mid-1882; in which a dude-like young man is described as a, “Dodo.” The use of “Dodo” to describe a stupid young man was consistent with the scientific name for the species of dodo, Ineptus, which means stupid or foolish in Latin. The use of “dodo,” in the sense of “a foolish person,” may have been new in 1882. The use of the name of a bird, “dodo,” to describe a “Dude,” was also consistent with a long-standing practice of using bird-imagery to describe fashion-conscious young men. Finally, the pronunciation of the word “Dude,” may have been created by its association with “Dodo” and “Didus,” and may have been influenced by the “-ood-” syllable in words like, “Fopdoodle,” “Fitzdoodle,” and “Fitznoodle,” “Flapdoodle,” “Yankee Doodle,” “Doodle,” or other “-oodle” word used to denote silliness or foolishness, generally, and sometimes dude-like characteristics, specifically.

![]() |

| Evening Times Republican (Marshalltown, Iowa), November 1, 1915, page 5. |

[i]Barry Popik and Gerald Cohen,

Dude Revisted: A Preliminary Compilation,

Comments on Etymology, Volume 43, Numbers 1-2, October – November 2013

[ii]Barry Popik and Gerald Cohen,

Dude Revisted: A Preliminary Compilation,

Comments on Etymology, Volume 43, Numbers 1-2, October – November 2013; Peter Reitan,

Dude: its ear attestation thus far (1879) is unreliable,

Comments on Etymology, Volume 43, Number 8, May 2014, page 2; Peter Reitan,

Another supposed 1879 source of dude was written later (‘Theresa and Sebatsian’ play),

Comments on Etymology, Volume 43, Number 8, page 4.

[iii]This article appeared in dozens of newspapers and magazines, in nearly identical form, although many of them also crediting the

Springfield Republican as the original source, and most of them referring specifically to the one town of “Salem, N. H.”

Some versions, however, paraphrase the article, and refer to use in, “some New England towns.”

[iv]Popik and Cohen, COE, Vol. 43, no. 1-2, page 10.

[v]Middlebury Register and Addison County Journal, April 27, 1883, page 6, column 4;

Spirit of the Age (Woodstock, Vermont), April 25, 1883, page 3, column 1.

Springfield, Massachusetts (where the original article was published), Middlebury, Vermont and Woodstock, Vermont are about 100 miles west-southwest, 100 miles northwest, and 150 miles northwest from Salem, New Hampshire, respectively.

[vi]The Sun (New York), November 14, 1886, page 8.

[vii]The Sun, November 11, 1883, page 5, column 7.

[viii]Dunphie may have spoken too soon, as Oscar Wilde, the aesthetic movement, and “dudes” were just around the corner when he wrote these words in 1878.

[ix]Although the genus-species,

raphus cucullatus, is more common today,

didus ineptus was in common use in the 1800s, and is still considered a synonym of the more common name.

[x] If, for that matter, the usage of “Yankee Doodle,” as an insult equivalent to “Sissy,” were widely known, “Yankee Doodle” may have had a larger influence, if any, than the two-syllable “dude” (“doody”), said to have been restricted to Salem, New Hampshire.

[xi]National Republican (Washington DC), August24, 1882, page 4;

Vermont Phoenix(Brattleboro, Vermont), September 1, 1882, page 1;

People’s Weekly and Prairie Farmer (Chicago, Illinois), Volume 54, Number 2, September 7, 1882, page 7;

Seattle Daily Post-Intelligencer (Washington), March, 4, 1883, page 4.

[xii]Northern Tribune (Cheboygan, Michigan), June 10, 1882, page 6;

The Evening Star(Washington DC), June 14, 1882, page 6;

Sedalia Weekly Bazoo (Sedalia, Missouri), July 4, 1882, page 2;

Millheim Journal (Millheim, Pennsylvania, July 20, 1882, page 1;

Stark County Democrat (Canton, Ohio), August 10, 1882, page 3; Evening Bulletin (Maysville, Kentucky), February 21, 1883, page 4; Donohoe’s Magazine, Volume 11, Number 6 (Boston, Massachusetts), June 1884, Page 543-544.

[xiii] The spelling does not appear to be a one-time typo, as the same spelling appears in each publication in which the story appeared.

[xiv]Omaha Daily Bee, November 23, 1882, page 3, column 3;

The County Paper(Oregon, Missouri), December 15, 1882, page 7, column 2.

[xv]News and Herald (Winnsboro, South Carolina), January 18, 1883, page 1;

Millheim Journal (Pennsylvania), February 1, 1883, page 1;

Columbus Journal (Nebraska), February 14, 1883, page 4.

[xvi] http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/popinjay

[xvii]Samuel Gross,

The Merchant Prince of Cornville: a Comedy, Chicago, R. R. Donnelley & Sons, 1896.

[xviii]John Edward Haynes,

Pseudonyms of Authors, New York, 1882, page 36. Fitznoodle, (Puck), B. B. Valentine.

[xix]The Spirit of the Public Journals, Volume 17, 1813, page 169.

[xx]Joel Collier,

Musical Travels Through England, London, G. Kearsly, 1774, page 30.

[xxi]John Lampe,

Amelia. A New English Opera, London, J. Watts, 1732. The play is described in a list of operas in the back of the book.

[xxii]John S. Farmer,

Americanisms, Old & New, London, T. Poulter, 1889, page 244.