Perhaps no song is more closely and fondly associated with Ireland than, Cockles and Mussels; the unofficial anthem of Dublin, which is also known as Molly Malone or In Dublin’s Fair City. The song chronicles the hard life of a second-generation (at least) fishmonger, “sweet Molly Malone”:

In Dublin City, where the girls they are so pretty,

‘Twas there I first met with sweet Molly Malone;

She drove a wheel-barrow, thro’ streets broad and narrow,

Crying “Cockles and mussles, alive, all alive.

Alive, alive o! Alive, alive-o!”

Crying, “Cockles and mussels, alive, all alive!”

She was a fishmonger, and that was the wonder,

Her father and mother were fishmongers too;

They drove wheel-barrows, through streets broad and narrow,

Crying, “Cockles and Mussels, alive, all alive.” –Cho.

She died of the faver, and nothing could save her,

And that was the end of sweet Molly Malone;

But her ghost drives a barrow, through streets broad and narrow,

Crying, “Cockles and mussels, alive, all alive.”

Henry Randall Waite, Carmina Collegensia: A complete Collection of the Songs of the American Colleges, with Selections from the Student Songs of the English and German Universitys, Boston, Ditson, 1876, page 73.

Background of the Song

Despite wide interest in the song, however, its origins have been little understood.

In 1988, around the time of Dublin’s Millennium Celebration, an anonymous “historian” claimed to have identified THE Molly Malone as a woman who died in Dublin in 1699.

Although no one really believed the claim, Dublin’s civic leaders took advantage of the “finding” to promote a new statue of Molly Malone.

The statue, now one of Dublin’s signature attractions, honors her as a working-class heror.

[i]

![]()

Skepticism of the claim that a specific Molly Malone from 1699 is THE Molly Malone is well founded. It is likely that thousands of Molly Malones have likely lived in Dublin over the centuries; and several of them may well have sold cockles and mussels. If that particular Molly Malone had been so noteworthy, you would think that there would be some mention of her sometime during the two-hundred years between her death in 1699 and the first appearance of the song in print in 1876; especially in light of the fact that the song quickly became popular soon afterward.

In 2010, Anne Brichton, a bookseller at Addybooks in Hay-on-Market, England caused a stir when she found a song entitled,

Molly Malone, in an undated book believed to have been published in about 1790.

The song was particularly intriguing as a precursor to

Cockles and Mussels because its “Molly Malone” is from Howth, a seaside village near Dublin; consistent with idea that Molly could have been a fishmonger in or around Dublin.

[ii] The book is

now in the collection of the Dublin Writers’ Museum.

Little else was known about the song, and the trail of the elusive origins of Cockles and Mussels went cold; until now.

New Information

The earlier Molly Malone was not a one-off, printed in one book and soon forgotten. It was a very popular song throughout the mid-19th century; appearing in print regularly from as early as 1817 through about 1880. Its popularity seems to have declined shortly after Cockles and Mussels became well known; I could only find three references to the song after 1885. You might think that there was only room for one Molly Malone in this town.

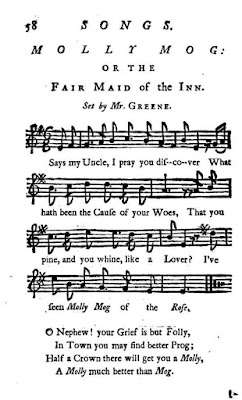

But wait, that’s not true. There were, in fact, at least three songs featuring characters named Molly Malone in print during the early 1800s and into the 1870s. Although none of those songs mentions cockles or mussels or fish, there are other similarities that tie all of the songs together. The numerous, early Molly Malone songs may, in turn, have been influenced by an even earlier song, Molly Mogg: Or, the Fair Maid of the Inn, which was co-written by Dublin-born satirist, Jonathan Swift.

But a more immediate precursor to Molly Malone, perhaps the missing link in the search for her origins, is a song published fifty years before the earliest known version of Cockles and Mussels. The song, Pat Corney’s Account of Himself, sings the praises of an Irish woman from a “city where the girls are so pretty,” who cries, “oysters, and cockles, and muscles for sale.”

There is also historical evidence that shows that several of the signature phrases in Cockles and Mussels were already well-established. The phrase, “Dublin’s fair city” was an idiomatic expression used to refer to Dublin long before the song was written. The historical record shows that fishmongers throughout Britain routinely sang the line, “cockles and mussels, alive, alive-O!” throughout the early- and mid-1800s. In the days before refrigeration, having live seafood was a big selling point. Evidence of the hard lives of street vendors during the period paints a picture of circumstances in which, dying of “the fever,” was a genuine concern.

The Earliest Known Version of “Cockles and Mussels”

The earliest known version of “Cockles and Mussels” in print was published in Boston in 1876.

[iii] Although the first line was slightly different than the version sung today (it begins, “In Dublin City,”), the traditional opening line, “In Dublin’s Fair City,” may be how it was actually sung.

The fline appears in a description of a performance of the song at a Harvard University alumni event that took place in 1881:

Song by Nathaniel S. Smith, together with a chorus by the Club. It was “Dublin’s Fair City, where the Girls are so pretty,” but with the substitution of “Boston” for “Dublin.”

The Harvard Register(Cambridge, Massachusetts), Volume III, Number 3, March, 1881 page 156.

The song appeared in a section of the songbook entitled,

Songs from English and German Universities, so it presumably is of British origin.

The next-earliest versions in print are from 1884; one published near Boston,

[iv]and a second in London that same year.

[v] The version from London reportedly provides the first hint of authorship of the piece:

[T]he 1884 London version describes the piece as a 'comic song' written and composed by James Yorkston and arranged by Edmund Forman. The latter version further acknowledges that the song was reprinted by permission of Messrs Kohler and Son of Edinburgh, so there must have been at least one earlier edition published in Scotland, which may well have been the original.

A later-published version, from

The Scottish Students’ Song Book (1897)

[vi], also credits Yorkston, a Scottish songwriter, supporting the attribution; so perhaps Yorkston, a Scotsman, actually did write the song.

Another song entitled,

Cockles and Mussels, with a different melody, different lyrics, and different composer, was reportedly published in London in 1876.

The song, set in London, featured “cockles and mussels” sold by a decidedly less romantic character, “Jim the Mussel Man.”

[vii] It is not, however, clear which of the two songs was published first.

Early Influences

There are several earlier songs, poems, and historical facts that may have influenced Cockles and Mussels. The line, “In Dublin’s fair city,” (as well as “In London’s fair city”) appear in earlier songs. The phrase, itself, was also a traditional, idiomatic way to refer to Dublin. The line, “where girls are so pretty,” was used fifty years earlier in a song about a woman from an Irish “city where the girls are so pretty” who cries, “oysters, and cockles, and muscles for sale.” A character named Molly Malone was featured in at least three songs that pre-date Cockles and Mussels by several decades. And, finally, the refrain, “cockles and mussels, alive, alive-O!” is taken from real life; it is documented that fishmongers in Ireland, Scotland and England sang the same lines on the street to advertise their wares.

In Dublin’s Fair City

The use of the phrase, “In Dublin’s fair city,” was not new in 1876; the phrase had been used in association with Dublin throughout the first half of the 1800s; frequently set apart with quotation marks denoting that it was a known, idiomatic expression.

The phrase “Dublin’s fair city” was used in an “Irish” “joke” that pokes fun at starvation, Catholicism, and Ireland, generally.

The joke appears in print as early as 1829, and again in various sources in at least 1846, 1868 and 1888:

[viii]

Family Reckoning.

Two Irishmen lately met, who had not seen each other since their arrival from Dublin’s fair city. Pat exclaimed, “How are you, my honey; how is Biddy Sulivan, Judy O’Connell, and Daniel O’Keefe?” “Oh! My jewel,” answered the other, “Biddy has got so many children that she will soon be a grandfather; Judy has six, but they have no father at all, for she never was married. And, as for Daniel, he’s grown so thin, that he is as thin as us both put together.”

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, Volume 13 (1829), page 96.

The phrase was also used in more literary sources.

A novel written by Lord William Pitt Lennox (an eyewitness to the Battle of Waterloo and aide-de-camp to the Duke of Wellington) includes a kind of

Trains, Planes and Automobiles (make that Horse, Chaise and Packet) description of the nearly seven day trip from London to Dublin in the days before rail service and steamships:

I only allude to my journey to draw a comparison between the travelling then in vogue and that of the present day. At the former period, starting every morning at half-past seven, and never stopping except to change chaise and horses, and for refreshments, until eight o’clock in the evening, we were five days upon the road: the sailing-packet varied in its passage, according to the wind, from ten to eight and forty hours: an hour more took us to Dublin’s fair city.

Percy Hamilton; or, The Adventures of a Westminster Boy, London, W. Shoberl, 1851, Volume 1, page 145.

An Irish writer, writing in 1879, suggests that the phrase may have been used as early as the 1790s:

Dublin Ninety Years Ago

One of the many ventures in Irish periodical literature which have at various periods been launched in Dublin was that entitled Anthologia Hibernica. This magazine was published monthly during the years 1793-4, by Richard Edward Mercier & Co., of Anglesea-street. It usually contained articles upon Irish antiquities and literature, reviews of new books, some mathematical and arithmetical problems, and extensive “poet’s corner,” and also each month a summary of the local events of importance during the previous one. It is this poritno of its contents which best repays perusal now, for in many ways it casts much light on what manner of thing life, political and social, was in “Dublin’s fair city” during the days of the Parliament.

The Irish Monthly (Dublin), Volume 7, 1879, page 474.

The phrase, “London’s fair city,” also shows up in a few sources, as early as the 1700s, but does not seem to have been as common. Interestingly (perhaps coincidentally), an early use of the phrase, “London’s fair city,” appears in a song about a woman named Molly Lapel, which, in turn, was based on song called, Molly Mogg, a song which may feature in the distant influences on Cockles and Mussels (more on that later).

There is at least one song that pre-dates Cockles and Mussels which begins, “In Dublin’s fair city.” The entire opening line nearly rhymes with the opening line of Cockles and Mussels (“In Dublin’s fair city, where girls are so pretty,”) suggesting, perhaps, some an influence on Cockles and Mussels. The song, about an inept officer in the army reserve corps, was published in 1813:

In Dublin’s fair city, so gay and so frisky,

So famous for Heroes, so famous for whisky,

Lived a Captain so bold, if the truth you’ll believe in,

That scarce had his fellow – brave Captain M’Nevin.

Captain M’Nevin, Captian M’Nevin:

Och! The Prince of a Captain was Captain M’Nevin.

Captain M’Nevin; or The Warrior’s Fireside at the Moment of Invasion (sung to the tune of Corporal Casey

[ix]); from Ebenezer Picken,

Miscellaneous poems, songs, etc. Partly in the Scottish dialect, with a copious glossary, Edinburgh, J. Clarke, 1813, page 82.

The melody of

Corporal Casey, the tune who which

Captain M’Nevinwas sung, is in 6/8 time, just like

Cockles and Mussels; but the melody was different.

[x] Corporal Casey's melody, however, is nevertheless mostly recognizable; much of it is nearly identical to the stock Irish jig which is usually called,

The Irish Washerwoman. The refrain

, “Capatin M’Nevin, Captian M'Nevin . . .” seems to play a similar role in

Captain M'Nevin as “alive-alive, O, alive-alive, O . . . .” does in

Cockles and Mussels.

The Missing Link - Where Girls are so Pretty

Fifty years before publication of the earliest know version of Cockles and Mussels, the apparent missing-link between Cockles and Mussels and the early Molly Malone songs appeared in print. In the song, Pat Corney is on the search for the perfect wife. He finds her selling shellfish in an Irish city, “where the girls are so pretty” and she cries, “oysters and cockles and mussels for sale.” Although she once entertained the idea of marriage, she is now married to herself, and spurns his advances.

The meter of the song fits quite nicely into the traditional melody of Cockles and Mussels. Eerily, perhaps, the song also foreshadows the statue erected in her honor one-hundred and sixty years later.:

Now it’s show me that city where girls are so pretty,

Because I’m in want of a wife you must know,

If she is but willing, I swear I’ll be killing,

And make her my wife whether she will or no.

Now it chanced as one day I looked out for a wife,

I ‘spied a dear creature, the joy of my life;

There she stood all alone, like a statue so pale,

Crying oysters, and cockles, and muscles, for sale.

Pat Corney’s Account of Himself(from, The Universal Songster: or, Museum of Mirth; forming the most complete, extensive, and valuable collection of ancient and modern songs in the English language with a copious and classified index, Volume II, , London, John Fairburn, 1826, page 19).

The song was widely available in Britain and the United States for decades.

The three-volume set,

The Universal Songster, was reprinted in England and the United States, in nearly identical form, in 1832, 1834, and 1878.

[xi] The song may not have been very popular, however; I could not find any reference to the song other than the one in

The Universal Songster.

Nevertheless, the striking similarity between the songs almost certainly suggests that elements of

Cockles and Mussels were borrowed from an earlier tradition, if not from

Pat Corney, directly.

Cockles and Mussels may also have been influenced by the regular use of the name, Molly Malone, in several songs about Irish women.

Sweet Molly Malone

There are at least three songs that feature a character named Molly Malone that pre-date the earliest known version of

Cockles and Mussels by several decades;

Molly Malone (between 1807 and 1817),

The Widow Malone (1809), and

Meet Me Miss Molly Malone (by 1836).

Molly Malone and

The Widow Malone share some similarities with

Cockles and Mussels, other than just the name.

The song,

Meet Me Miss Molly Malone, was written later (1840), apparently in the United States, and does not appear to be an influence on

Cockles and Mussels.

[xii] It does, however, support the notion that the name, Molly Malone was a well-known, popular name for Irish women in song during the period.

Molly Malone (1807-1817)

If you turn to page 350 of Volume II of The Universal Songster, the same volume that includes Pat Corney’s Account of Himself, you will find a song entitled, Molly Malone; the same song discovered in 2010. Although that book discovered in 201 was estimated to have been printed in about 1790, other evidence suggests that the song was likely written between about 1807 and 1817.

The earliest version of Molly Malone I have seen is from 1817. Like Pat Corney’s Account of Himself, the song laments a man’s inability to marry a woman; in this case, “sweet Molly Malone”:

Molly Malone.

By the big hill of Howth,

That’s a bit of an oath,

That to swear by I’m loth,

To the heart of a stone,

But be poison my drink,

If I sleep, snore, or wink,

Once forgetting to think,

Of your lying alone.

Och! It’s how I’m in love

Like a beautiful dove,

That’s sits cooing above,

In the boughs of a tree:

It’s myself I’ll soon smother,

In something or other,

Unless I can bother,

Your heart to love me,

Sweet Molly, sweet Molly Malone,

Sweet Molly, sweet Molly Malone.

TheHibernian Cabinet; a Selection of all the Most Popular Irish Songs, that have been lately written, London, T. Hughes, 1817, pages 76-77.

Pat Corney and Molly Malone also share references to doves in common. Whereas the woman selling “cockles and mussels” to Pat Corney asked him to buy, “with the voice like a dove,” the narrator of Molly Malone is in love, “like a beautiful dove, that sits cooing above”

OK, I admit it, they are not quite identical; but still; the similarities are interesting. And even if you dismiss the similarities in the plot-line and references to doves as too tenuous, Molly Malone did, at least, introduce the character of Molly Malone to popular song sometime between 1807 and 1817.

The sub-title of the 1817 book in which Molly Malone appears, “the most popular Irish Songs, that have been lately written,” suggests that the song was considered relatively new in 1817. This would be consistent with other references attributing the song to the English songwriter, John Whitaker, who is

“known as a writer of occasional songs introduced in musical plays at the principal theatres between 1807 and 1825”

[xiii]:

St. Clement’s, Eastcheap

Three Church musicians, each distinguished in his way, have held the post of organist at St. Clement’s at various times during the last two centuries viz. Edward Purcell (d. 1740), youngest son of Henry Purcell the younger; Jonathan Battishill, composer of many chants and anthems still in use, and an organist of most sterling qualities, specially good at extemporaneous playing (d. 1801); and John Whitaker (d. 1847), the composer of many songs and ballads, some of which acquired a large share of popularity, as e.g., O Say not Woman’s Heart is Bought; My poor Dog Tray, andMolly Malone.

T. Francis Bumpus,

London Churches Ancient & Modern, London, T. W. Laurie, 1908(?)

[xiv], page 311.

Whitaker’s Molly Malone proved to be very popular. The song was so well-known and popular in 1831 that a Scottish writer referred to the song as, “Our old acquaintance Molly Malone.”

I have included an extended excerpt from the review to give you a taste of the casual ethnic bigotry of the day:

If we are to judge of Irish songs by this collection [(The Shamrock; a Collection of Irish Songs, Glasgow, Atkinson & Co., 1831)], we must say, that the words in general are by no means worth of the music. The simple Irish melodies are perhaps superior even to those of our own Scotland, in rich and varied pathos, sweetness, and refinement of sentiment. This is probably to be attributed to the deeper tone of feeling which pervades the native Irish airs. “In listening to Irish music,” Mr. Weekes has remarked in his preface, “we are struck with an exquisite melancholy in its character – a melancholy so profound, that the finest feelings of the human heart must indeed have been grievously wrung to produce such an inimitable pathos.” Yet, with all the strange inconsistency which so particularly distinguishes Irishmen, we frequently find the saddest airs wedded to words of a light and grotesquely humorous kind. The truth is, music, especially of a simple character, starts more spontaneously into existence, and flows more directly from the heart, than poetry, which is more indicative of previous study and intellectual exertion. Now, the native bards of Ireland, - Heaven help them! – have never been conspicuous either for their studious habits, or the strength of their intellectual faculties; and, to speak plainly, their indigenous song-writers, of course with the splendid exception of Moore, are most deservedly a nameless and unknown herd. Yet now and then we do meet with a few verses that please us, from their being full of the genius of the people. Of this description is the song entitled, Ma Collenoge. . . .

Our old acquaintance Molly Malone is also redolent of the Emerald Isle.

The Edinburgh Literary Journal, Volume 5, 1831, page 43.

Whitaker’s song was so popular that its melody was used in several later songs. One of those songs, The Hermit’s Philosophy (Charles O’Flaherty, Trifles in Poetry, including, Hermit’s Minstrelsy, Dublin, R. Carrick, 1821, page 33) was written by an Irishman, so the tune, although apparently written by an Englishman, seems to have been approved of and appreciated by at least one Irish writer.

A review of another song written to the tune of Molly Malone also attributes the melody to Whitaker:

This song was written to Whittaker’s beautiful Irish air, “Molly Malone,” which has all that sweetness and impassioned burst of feeling that so peculiarly distinguish that highly-gifted composer.

The Metropolitan Magazine(London), Volume 43, May 1845, page 46.

Whitaker’s Molly Malone was not the only early song with a character named Molly Malone. It may not have even been the earliest. The heroine of The Widow Malone (1809) was also a well-known Molly Malone.

Widow Malone (1809)

If you turn to page 51 of, The Shamrock, a Collection of Irish Songs, the same book reviewed by the Scottish writer who approved of Whitaker’s Molly Malone, you will find a song entitled, The Athlone Landlady. This is the earliest version of the The Widow Malonethat I could find in print. Although her name is Katty in this version, she is referred to as Molly Malone in most other versions.

The song was apparently very popular in its time; it was featured in several plays, mentioned in a number of books, and reprinted in numerous songbooks throughout the mid-1800s. As in Pat Corney’s Account of Himselfand Molly Malone, this song sings the praises of a desirable, yet stand-offish Molly Malone. The twist here, however, is that the widow succumbs to a man of action; the first suitor to just kiss her, instead of trying to woo her:

“Did ye hear of the widow Malone, Ohone?

Who lived in the town of Athlone – Alone?

Oh! She melted the hearts

Of the swains in them parts,

So lovely the widow Malone, Ohone?

So lovely the widow Malone,

“Of lovers she had a full score, Or more;

And fortunes they all had galor. In store.

From the minister down

To the clerk of the crown,

All were courting the widow Malone, Ohone?

All were courting the widow Malone

But so modest was Mrs. Malone, ‘Twas known,

No one ever could see her alone, Ohone?

Let themogle and sigh,

They could ne’er catch her eye,

So bashful the widow Malone, Ohone?

So bashful the widow Malone,

“’Till one Mister O’Brien from Clare, How quare?

It’s little for blushin’ they care Down there,

Put his arm round her waist,

Gave ten kisses at laste,

‘Oh,’ says he, you’re my Molly Malone My own;

‘Oh,’ says he, you’re my Molly Malone My own;

Oh,’ says he, you’re my Molly Malone.

“And the widow they all thought so shy, My eye!

Ne’er thought of a simper or sigh, For why?

But ‘Lucius,’ says she,

‘Since you’ve made now so free,

You may marry your Mary Malone, Ohone?

You may marry your Mary Malone.’

“There’s a moral contained in my song, Not wrong;

And one comfort it’s not very long, But strong:

If for widows you die,

Larn to kiss, not to sigh;

For they’re all like sweet Mistress Malone, Ohone?

Oh! They’re all like sweet Mistress Malone.”

Although I could not find a version of the song in print from before 1830, the noted Irish author, composer, musicologist and historian,

W. H. Grattan Floodattributed the song to Daniel O’Mara, a Dublin playwright, publication date in 1809.

[xv]

The reason that Charles Lever had wrongly been credited for writing

The Widow Malone was that it was sung by a character in his 1840 book,

Charles O’Malley; the Irish Dragoon.

[xvi] In the story, soldiers who had once been stationed in County Cork claimed to have written the song about the landlady of an inn where they had stayed.

Coincidentally (or not) another widow Malone, also a landlady of an inn frequented by soldiers, features prominently in book written ten years earlier; the widow’s name? “Sweet Matty Malone”:

Her dress, if such it may be called, was merely short stays, one petticoat, and a scanty shawl thrown over her shoulders, leaving exposed to the view the most beautiful though lusty pair of arms in the kingdom. In this state, in such a place, and such an hour, chance threw in my way the fresh and buxom widow, looking all freshness, more like a Dutch Venus of twenty-five than the humble hostess of an Irish sheebeen of forty. My ghost could not have alarmed her more than did my sudden appearance, as I glided into the dim region of curds and cream. A faint “O Lord!” and then, “darling jewel, lave me,” was all she could utter. The churn was forsaken. I felt bound to explain, and apologise for my intrusion. She heard me in silence, and hung her head: the full-blown rose, expanding its inmost leaf to the balmy breeze of the morn was not more sweet. What a situation!

Oliver Moore, The Staff Officer: or, the Soldier of Fortune: a Tale of Real Life, London, Cochrane and Pickersgill, 1831, page 26.

A desirable landlady named Molly M. was also featured in a popular song that written in the 1720s and was well known and popular throughout the 18thcentury.

MOLLY MOGG (1726)

In 1726,

[xvii]the Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist and political pamphleteer,

Jonathan Swift (who wrote

Gulliver’s Travels) and the famous 18

th Century poet,

Alexander Pope (famous for his translations of the Homer’s

Iliadand

The Odyssey) teamed up to write a silly song about the daughter of the innkeeper of the Tavern at the Sign of the Rose, in Workingham, Berkshire.

[xviii]As was the case with the

The Widow Maloneand

Molly Malone eighty years later, the song is one of desire and unrequited love for a woman named Molly M.:

Molly Mogg: Or, the Fair Maid of the Inn.

. . .

I know that by Wits ‘tis recited,

That Women at best are a Clog:

But I’m not so easily frighted,

From loving of sweet Molly Mogg.

. . .

The School-Boy’s Desire is a Play-Day,

The School-Master’s Joy is to flog:

The Milk-Maid’s Delight is on May-Day,

But mine is on sweet Molly Mogg.

. . .

When she smiles on each Guest, like her Liquor,

Then Jealousy sets me agog,

To be sure she’s a Bit for the Vicar,

And so I shall lose Molly Mogg.

The Musical Miscellany, Being a Collection of Choice Songs, set to violin and flute, London, John Watts, Volume 2, 1729, pages 58-61.

Molly Mogg was not a widow, but she was single.

And, although she was the daughter of the landlord, she was likely involved in running the Inn.

She operated the Inn on her own (she never married) from the time of her father’s death in 1736 to her own death in 1766.

She was famous when she died that a notice of her death appeared in

The London Magazine.

[xix]

I.

The Muses quite jaded with rhyming,

To Molly Mogg bid a farewell,

But renew their sweet melody chiming,

. . .

VII.

Of all the bright beauties so killing,

In London’s fair city that dwell,

None can give mu such joy, were she willing,

As the beautiful Molly La--l.

A Ballad, by the Earls of Chesterfield and Bath (in, James Frederick Dudley Chrichton-Stuart, The New Foundling Hospital for Wit, London, J. Debrett, 1784, page 225).

Molly Mogg’s popularity is reflected in a poem published in 1760, which refers to a man as, “a Male Molly Mogg.” Also, a racehorse named Molly Mogg was active during the 1790s.

Due to the popularity of Molly Mogg, and its regular use in other contexts, it seems plausible that the person or persons who wrote Molly Malone or The Widow Malone could have had Molly Mogg in mind when naming the Irish woman in their respective songs. The more obvious similarities between the landlady, Molly Mogg, and Molly Malone, the Athlone Landlady, lends an extra degree of plausibility to the connection.

It is not a huge leap of faith to imagine that the popular “Molly Mogg” theme could have been revamped and revised any number of times, with elements of it eventually finding their way into The Widow Malone, Molly Malone, and later Pat Corney; any one or all of which could have influenced Cockles and Mussels. A “fair city,” “Molly M.,” unrequited love; perhaps it’s all sheer coincidence; or perhaps it’s part of a continuous pop-cultural thread from Molly Mogg, through Molly Lepel, Widow Malone, Molly Malone, and the “cockles and muscles” seller in Pat Corney’s Account of Himself, and ultimately to the beloved version of “Cockles and Mussels” we know today.

Cockles and Mussels, Alive-alive-O!

In 18th and early-19th century Britain, street vendors often hawked their wares by singing. Their songs, chants, and tunes frequently found their way into popular song. The songs, and the characters associated with the songs, were so popular that the sale of prints showing street vendors and their cries, were popular during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Mr. Kidson’s “Cockles and Mussels” cry is like part of the “Fly-paper” cry noted by myself, and his tune to “Young Lambs to Sell” suggests an old dance-air; it has a good deal of likeness to “Of all the birds” from Deuteromelia, 1609 (see Chappell’s Popular Music). – L.E.B.

Journal of the Folk-Song Society(London), Volume 4, Number 15, page 105

The cries themselves are preserved in old comedies, in old ballads, and principally in the cries attached to old woodcuts illustrating the criers. These woodcuts used to be hawked about the streets, and there are numerous series, with such names as “The Manner of Crying Things in London.” We are all familiar with the famous song Caller Herrin’! and with the song equally well known which immmortalises the cry of Cockles . . . and mussels . . . Alive, Alive, O!. . . . .

John O’London, London Stories, Volume 1, London, T. C. and E. C. Jack, 1911, page 2.

Thirty years ago a trade was carried on by women and boys bringing cockles, whelks, and mussels from peffer Sands to Haddington for sale. “Cockles and mussels, alive, alive, O!” was often called in Haddington streets. This trade is now defunct.

John Martine, Reminiscences of the Royal Burgh of Haddington, Edinburgh and Glascow, John Menzies & Co., 1883, page 110.

Frederic Kenyon Brown, born in 1882, in reminiscing on his youth, remembered his uncle Stan in Northern England shouting the less lyrical:

Mussels and cockles alive! Buy ‘em alive! Kill ‘em as you want ‘em!

Al Pridy (Frederic Kenyon Brown, Through The Mill, the Life of a Mill Boy, Boston, Pilgrim Press, 1911, page 8.

A description of fishmongers in action at Billingsgate, London, in 1851 provides a good picture of what a similar market in Dublin may have looked like during the same period:

Of the Street Sellers of Fish: Billingsgate.

Many of the costers that usually deal in vegetables, buy a little fish on the Friday. It is the fast day of the Irish, and the mechanics’ wives run short of money at the end of the week, and so make up their dinners with fish; for this reason the attendance of the costers’ barrows at Billingsgate on a Friday morning is always very great. . . . The whole neighborhood is covered with the hand-barrows, some laden with baskets, other with sacks. Yet as you walk along, a fresh line of costers’ barrows are creeping in or being backed into almost impossible openings; until at every turning nothing but donkeys and rails are to be seen. The morning air is filled with a kind of seaweedy odour, reminding one of the sea-shore; and on entering the market, the smell of fish, of whelks, red herrings, sprate, and a hundred others, is almost overpowering. . . .

All are bawling together – salesmen and hucksters of provisions, capoes, hardware, and newspapers – till the place is a perfect Babel of competition. ‘Ha-a-ansome code! Best in the market! All alive! Alive! Alive O!’‘Ye-o-o! e-o-o! here’s your fine Yarmouth bloaters! . . ‘Turbot! Turbot! All alive!Turbot!’ . . . ‘Hullo! Hullo here! Beautiful lobsters! Good and cheap! Fine cock crabs all alive O’ . . . ‘Here, this way! This way for splendid skate! Skate O! skate O! ‘Had-had-had-had-haddick! All fresh and good!’ . . . ‘Ahoy, ahoy here! Live plaice! All alive O!’ . . . ‘Eels O! eels O! Alive! Alive O!’ . . . Fish alive! Alive! Alive O!

Henry Mayhew, Mayhew’s London; being selections from ‘London labour and the London poor’, London, Spring Books, undated (but with comment, “First published in 1851”), pages 102-103.

![]() |

| London street vendor with barrow; Old London Street Cries, London 1888. |

Similar street selling traditions were found in American cities in 1850:

![]() |

| Oyster Seller |

![]() |

| Crab Seller |

![]() |

| Pompey the Fishmonger |

Croome, City Cries: or, a Peep at Scenes in Town, Philadelphia, G. S. Appleton, 1850.

The Hard Life of Cockles and Mussels Sellers

Mayhew’s London, the book that listed many of the street cries quoted above, also provides some insight into the hard life of street merchants; including the life of a woman whose “mother before her” was also a street merchant. The book also gives some insight as to why a self-sufficient, independent street vendor might consciously avoid entanglements with men:

The costermongers, taken as a body, entertain the most imperfect idea of the sanctity of marriage. To their undeveloped minds it merely consists in the fact of a man and woman living ogether, and sharing the gains they may each earn by selling in the street. . . . .

At about seven years of age the girls first go inteo the streets to sell. A shallow-basket is given to them, with about two shillings for stock-money, and they hawk, according to the time of year, either oranges, apples, or violets; some begin their street education with the sale of water-cresses. . . .

The life of the coster-girls is as severe as that of the boys. Between four and five in the morning they have to leave home for the markets, and sell in the streets until about nine. Those that have more kindly parents, return then to breakfast, but many are obliged to earn the morning’s meal for themselves. . . .

The Life of a Coster Girl

The one I focused upon was a fine-grown young woman of eighteen. . . . Her plaid shawl was tied over the breast, and her cotton-velvet bonnet was crushed in with carrying her basket. . . . .

‘My mother has been in the streets selling all her lifetime. Her uncle learnt her the markets and she learnt me. When business grew bad she said to me, “Now you shall take care on the stall, and I’ll go and work out charing.” . . . I always liked the street-live very well, that was if I was selling. I have mostly kept a stall myself . . . .

The gals begins working very early at our work; the parents makes them go out when a’most babies. . . .

‘I dare say there ain’t ten out of a hundred gals what’s living with men, what’s been married Church of England fashion. I know plenty myself, but I don’t, indeed, think it right. It seems to me that the gals is fools to be ‘ticed away, but, in coorse, they needn’t go without they likes. This is why I don’t think it’s right. Perhaps a man will have a few words with his gal, and he’ll say, “Oh! I ain’t obligated to keep her!” and he’ll turn her out; and then where’s that poor gal to go? Now, there’s a gal I knows as came to me no later than this here week, and she had a dreadful swole face and a awful black eye; and I says, “Who’s done that?” and she says, says she, “Why, Jack” – just in that way; and then she says, says she, “I’m going to take a warrant out to-morrow.” Well, he gets the warrant that same night, but she never appears again him, for fear of getting more beating. That don’t seem to me to be like married people ought to be. Besides, if parties is married, they ought to bend to each other; and they won’t , for sartain, if they’re only living together.that poor gal to go?

Mayhew’s London, pages 91-93.

A book about resolving the tensions between England and Ireland published in 1868 illustrates why selling cockles and mussels may have been particulary difficult in Ireland:

Not far from the town where I am now writing, a predecessor of one of Ireland’s best land-lords had the shameful meanness to put bailiffs on the strand to exact fourpence from each person who took a can and a spoon to collect cockles; in case a rake was used for gathering the bivalves, eight pence were exacted. These sums were charged every time the cockle-pickers went to collect. This titled landlord was entitled “the cockle lord.” I need hardly say that the present excellent proprietor does not exact cockle-rent.

Henry O’Neill, Ireland for the Irish: A Practical, Peacable and Just Solution, Ireland, TRubner and Co., 1868, page 78.

Conclusion

The Molly Malone of Cockles and Mussels reflects the true conditions and circumstances of fishmongers in early- to mid-19th century Britain, whether or not she is fictional or based on a particular person. Although apparently written by a Scottish songwriter, many elements of the song are decades older; and some of those elements may have Irish roots.

Regardless of the specific origins of Cockles and Mussels, nothing can erase what the song has come to represent for Dubliners, Irishmen and the entire Irish Diaspora during the ensuing one-hundred and forty-some odd years. But the details of the pop-culture history, and actual history, behind Cockles and Mussels, may provide an even greater appreciation for the song and all of the hard-working street vendors and working-class heroes it honors.

[ii]Howth was known as a place where shellfish could be purchased.

The last reference to the song in print, that I could find, includes a long discussion about the quality of Howth’s oysters.

John d’Alton’s,

The History of County Dublin (1838), specifically mentions Malahide (just a few miles from Howth) as a particularly good place to collect cockles; presumably Howth had cockles as well.

[iii] Henry Randall Waite, Carmina

Collegensia: A complete Collection of the Songs of the American Colleges, with Selections from the Student Songs of the English and German Universitys, Boston, Ditson, 1876, page 73.

[iv]William H. Hills,

Students’ Songs, Comprising the Newest and Most Popular College Songs, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Moses King, 4

th Edition, 1884 (the first edition was published in 1880; it does not indicate which songs were in the first edition).

[vi] A. G. Abbie,

Scottish Students’ Song Book, London, Bayley & Ferguson, 1897, page 269.

[viii]The New Parley Library (London), Volume 1, 1844, page 395;

The Merry Companion for all Readers, Halifax, William Nicholson & Sons, 1868, page 86;

The Journal of Solomon Sidesplitter, Philadelphia, Pickwick & Company, 1884, page 180.

[ix]Corporal Casey, written by Dr. Arnold, was first performed by Mr. Johnstone, in the part of an Irish character named O’Carroll, in the play,

The Surrender of Calais, at the Theatre Royal, at Haymarket, London, which premiered on June 30, 1791.

See,

The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, volume 89, August 1791, page 142.

[x]See,

One Hundred Songs of Ireland, Boston, Ditson, 1859, page 49..

[xi]Only the three volumes of the first edition, dated 1825 or 1826, were published with the year of publication printed on the title page.

The dates of the later editions were provided in the respective electronic databases where I accessed them.

All of the volumes are available from several different libraries.

Nevertheless, the years 1832, 1834 and 1878 recur consistently in all of the various records, suggesting that the dates were known to the record keepers.

[xii] The song,

Meet Me Miss Molly Malone, appears in several American songbooks from as early as 1833.

The song was written as “Irish” humor, sung to the tune of

Meet Me By Moonlight Alone.

Whereas

Meet Me by Moonlight Alone is full of romantic notions about moonlight,

Meet Me Miss Molly Malone finds humor in the hunger of a poor, destitute Irishman. Compare, “For though dearly a moonlight I prize, I care not for all in the air, If I want the sweet light of your eyes. So meet me by moonlight alone,” with, “then come if my dear life you prize; I’d have liv’d the last fortnight on air, But you sent me two nice mutton pies. Then meet me, Miss Molly Malone.”

[xiii]Sidney Lee

(Ed.),

Dictionary of National Biographies, Volume 61, London, Smith, Elder & Co., 1900, page 18.

[xiv]This undated volume includes textual references to events in 1905, 1906 and 1907, but none to anything in 1908 or afterward.

[xv]The Athenaeum, 1906:2, Number 4114, September 1, 1906, page 243.

[xvi]The Dublin University Magazine, Volume 16, Number 91, July 1840, page 62.

[xvii]In a piece in

Notes and Queries(Volume 95, January 16, 1897, page 57), Colonel William Francis Prideaux gave the first publication of

Molly Moggas,

Mist’s Weekly Journal, No. 70, 27 August, 1726.

[xviii]William West,

Tavern Anecdotes, and Reminiscences of the Origin of Signs, Coffee Houses, &c., New York, S&DA Forbes, 1830, pages 162-165.

[xix]The London Magazine, or Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, Volume 35, April 1766, page 214 (Deaths . . . March 8 – Miss Molly Mogg, well remembered from the song bearing her name.