Part II

Naughty Doings in the Midway Plaisance

. . .

On the Midway, the Midway, the Midway Plaisance,

Where the naughty girls from Algiers do the Kouta-Kouta dance.

Married men without their wives give a longing glance

At all the naughty doings on the Midway Plaisance.

. . .

An old man said, “I’d like to get an introduction there;”

He sent his card around by way of chance,

And on it wrote, “Oh, darling, my naughty angel fair,

Teach me to do your ‘Kouta-Kouta’ dance.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 23, 1894, page 5.

The exotic, erotic form of dancing popularized at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 would later become known as, the “coochie-coochie” or “hoochie-coochie.” When the same dance was popularized three years earlier, at the Paris World’s Fair, the dance was generally referred to as, the “stomach dance” or danse du ventre (French for dance of the stomach). And even during the Chicago fair, the dance was generally referred to as, danse du ventre, “mussle dance,” “stomach dance” or the “Midway dance.”

About one year before the Chicago World’s Fair, a dancer named “Avita” (or “Vita”), an Italian-American dancer who was educated in a convent in France, introduced a dance called, the “Kouta-Kouta,” in a Broadway play about a man who inherited his uncle’s harem when the uncle (as it turned out) faked his own death to avoid facing his first wife. Avita said she learned the dance in India from a Rajah’s favorite dancer. The dance may not have been precisely the same as a belly dance, but it was considered just as risqué, and was generally lumped in together with the other exotic dances that shocked and titillated American audiences.

Shortly after the fair closed, and occasionally during the fair, the name, “Kouta-Kouta” (or the like) became widely associated with Midway dances at the fair.

The name “Coochie-Coochie” first appeared in print about one year after the fair closed; apparently derived from “Kouta-Kouta” under the influence of the expressions, “kutchy, kutchy” and “hootchy, kootchy, kootchy,” which had been popular song lyrics from as early as 1863.

The transition from “Coochie-Coochie” to “Hoochie-coochie” may have been further influenced by a linguistic template favoring rhyming reduplication expressions that begin with “H”, like “helter skelter,” hocus pocus,” and “hodge podge”

[i]; and earlier such dancing girl-related expressions like, “hurdy gurdy,” “honky tonk” and “hula-hula,” all of which were in use before “hoochie coochie.”

The dancer named “Little Egypt,” who frequently gets credit for popularizing the dance at the fair, first appears in the written record within weeks after the fair closed. It is possible that she danced at the fair, but if she did, she did not appear to achieve any degree of notoriety. She did not become famous, or infamous, until taking her clothes off at a bachelor party thrown for one of P. T. Barnum’s grandsons in 1896.

After the Fair

When the Chicago World’s Fair closed in October of 1893, the dancers did not head back to Egypt, Algeria, Persia or other points of actual or purported origin. Some dancers stayed in Chicago at the Midway Plaisance, which remained open for more than a year after the fair. Other dancers, with and their promoters and entourage, picked up their tents and camels and packed off to other fairs. The success of the Chicago World’s fair soon gave way to the California Midwinter International Exposition of 1894 (opened in January 1894), the Northwest Interstate Exposition (opened August 1894), and the Cotton States Exposition (opened in September 1895). And some of the dancers would up in jail.

In the reporting of some of these fairs, the dance that would later be called the “coochie-coochie” or “hoochie-coochie,” was sometimes called the “kouta-kouta”; notably in relation to its performance in Boston and San Francisco. But the first big post-Chicago fair was held in New York; well, to be fair, it wasn’t really a new fair; it was a recreation of the Chicago fair.

New York City

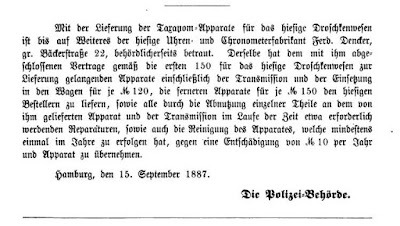

![]() |

| The Sun (New York), November 29, 1893, page 10. |

The “World’s Fair Prize Winners’ Exposition” opened at the Grand Central Palace in New York City on Thanksgiving Day of 1893; thirty days after the Chicago World’s Fair officially closed:

The main floor will be entirely filled with foreign exhibits, the native exhibits being on the first and second galleries. On the third gallery will be the Midway Plaisance features, including the streets of Cairo, the Javanese Village and the Oriental Café, with the Syrian dancing girls.

New York Tribune, November 29, 1893, page 12.

And, like clockwork, the Police intervened:

A decided commotion was caused in the Cairo Street last night when Inspector Williams rose from a seat near the stage, where Fareida was performing her “danse du ventre,” rather more fully clad than in Chicago, and, extending his arm, said, decidedly: “This show will not go on tonight or any other night.”

New York Tribune, December 3, 1893, page 4.

The action may have come as a surprise, since Anthony Comstock (who had formed the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice) “had seen the dance on Friday night and made no objection to it.”

It may also have come as a surprise to the dancer,

“Omene” (see Part I), who was then appearing at New York City’s Imperial Music Hall, and who was reportedly “far more suggestive and bold in her treatment of the dance than the women of the Midway Plaisance.”

[ii]

In order for force a test case and get a court ruling, the dancers went the next night in defiance of the police order; the police arrested them, and four dancers were fined $50. Disappointed courtroom crowds never got to see them dance:

![]() |

| New York Tribune, December 5, 1893, page 3. |

Zuleika Ziemman, eighteen years old, of Algiers; Zora Ziemman, seventeen years old, of Algiers, and Fatma Missgisch, twenty-two years old, of Algiers. Their New York residence is at 114 East Fortieth Street. They were charged with being public nuisances. The Dancers manager is Adolph Delacroix, a Belgian and a civil engineer, having spent a number of years in Algiers and Egypt. . . . Manager Delacroix said he was weary of New York, and would take his show elsewhere.

The Evening World, December 6, 1893, page 3.

So he packed up his dancers and shuffled off to Boston – founded by puritans – what could go wrong?

Boston

The “Kouta Kouta” dancers will no longer disgrace the Boston stage.

Like a surgeon’s knife, deftly wielded, the Post’s article yesterday morning cut out this and other abominations that have catered to depraved human nature at the Howard Atheneum.

Promptly seconding the Post’s demand yesterday morning came a petition of the leading organizations of Boston women calling for action.

The Boston Post, January 18, 1894, page 1.

![]() |

| The Herald (Los Angeles), January 18, 1894, page 1. |

![]() |

| Arizona Republican (Phoenix, Arizona), January 18, 1894, page 1. |

|

San Francisco

To capture or recreate the excitement and buzz generated by the Chicago fair, they recreated many of the same, successful elements. For example, the Midwinter Fair had a “Firth Wheel” (like the Ferris Wheel that debuted in Chicago) and an “electric tower” (the spittin’ image of the Eifel Tower and the smaller copy from Chicago). And, of course, they brought along some of the fair’s big money-makers, including the “Street in Cairo” and many of the same dancers:

At the Paris Exposition, in 1889, the Rue du Caire attracted a great deal of attention from visitors of all nationalities. At Chicago the idea was expanded, and developed into one of the greatest successes of that Exposition of great successes. As a result of these two experiments we have here in the Midwinter fair an oriental Village or Street in Cairo, complete and perfect in every detail. . . .

Two of the principal buildings of the Village are the theaters, the one called the Peruvian [(sic – read Persian)] Palace of the Bella Baya and the other Cairo Street Theater. It is here that the dancers and singers are to be seen and heard, those houris of the East, La Belle Baya, the Queen of Beauty, the bright particular star of the Persian Palace, Akoun Ben Eni, Ayesha, the soft-eyed, Soledad and Fatima, Enchantress of the Nile. Here also are the musicians under the management of Zithoun. In the Cairo Street Theater the visitor may see the sword dance and candle dance and the much talked of Danse du Ventre, performed by such stars of the East as Rachael of Beyrut, Ameede of Damascus and Feride of Egypt.

Official Guide to the California Midwinter Exposition in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, G. Spaulding & Co., 1894, pages 113-114.

![]() |

| The Morning Call, March 27, 1894. |

The dances the dancers danced at the Midwinter Fair in San Francisco were routinely called, the “Kouta-kouta”:

The kouta-kouta, as this dance is called, would shock a Puritan into death agonies. It is characterized by lascivious suggestiveness run mad, and the antics of a Carmencita are discounted by its languourous suppleness. Whatever wild Indians, Dervishes, Arabs, Kanakas, and scores of other specialties, can avail to make the show draw, is there. Those who are surfeited with the kouta-kouta can go a short distance and regale themselves with the even more indecent houla-houlaof the Hawaiian dance girls. “You pays your money and you takes your choice.”

The Herald (Los Angeles), February 1, 1894, page 4.

Several dancers in San Francisco were arrested – but were acquitted after performing their dances for an appreciative jury:

![]() |

| The Morning Call (San Francisco), April 10, 1894, page 12. |

When the Midwinter Fair ended, one reporter and a group of his friends hired some of the dancers for a private and (he believed) more authentic dance – in the nude:

On Saturday evening last a party of friends, including myself, had the famous kouta-kouta dance performed in private. The girls, who are devoid of all shame, danced before our party in an entirely nude condition, not a vestige of clothing remaining upon their persons. This is the only way in which one can get a glimpse of the dance as it is performed in oriental countries.

The Herald (Los Angeles), April 25, 1894, page 6.

No arrests were made.

Elsewhere

The “kouta-kouta” also showed up in Seattle, Washington, Albany, New York,

[iii]Brockton, Massachusetts,

[iv]and at the Westchester County Fair in White Plains, New York:

A loud-voiced man stood on the platform in front of a tent in which two alleged Kouta-Kouta girls were, and announced: “Ladies and gentlemen, within this tent is contained the two most beautiful girls who danced on the Midway Plaisance. They do the most wonderful dance on record, namely, the Kouta-Kouta dance of the Midway Plaisance.

The Sun (New York), September 27, 1894, page 5.

The “kouta-kouta” (by that name) was still being performed in Washington DC

[v]and Pittsburg

[vi]during 1895.

In late-1894 and again in 1896, two newspapers in Washington DC referred to the dance with an apparently transitional form of the word, midway between “Kouta-Kouta” and “Coochie-Coochie”:

The kutcha-kutcha dance, which was put on with the Reily & Wood show at Kernan's Theater, Monday night, was stopped yesterday by Mr. Kernan, who was much displeased with it.

Washington Post, December 5, 1894, page 6.

[vii]

A roaring farce entitled “Two New Wives,” a scene in the sultan’s harem, concluded the performance and gave opportunity for Florence Miller to do her sensational kutcha-kutcha dance.

The Morning Times (Washington DC), December 29, 1896, page 4.

But by late-1896, the expression “Coochie-Coochie,” which first appeared as early as late-1894, had almost completely erased “Kouta-Kouta;” and “Hoochie-Coochie” was starting to make inroads.

![]() |

Oscar Wilde’s Salomefeatured a “stomach dance” or “dance of the seven veils” on Broadway in 1893. The Early Work of Aubrey Beardsley, London, John Lane, 1920, page 148. |

Coochie-Coochie

The earliest example of “coochie-coochie” (or the like) that I could find, in the sense of an exotic, erotic dance, is from a fair in New Jersey; on the other side of New York City from White Plains, where the “kouta-kouta” was still in use:

VICE AND VLUGARITY AT A FAIR.

UNWORTHY FEATURES OF THE SOMERSET COUNTY AGRICULTURAL SHOW

Somerville, N. J., Sept. 13 (Special). – “Come, gents, walk right up and see the ‘Couchee-Couchee Dance.’ For gents only, remember; no ladies allowed.”

New York Tribune, September 14, 1894, page 5.

In February of 1895, a high-society “French Ball” in New York City featured a woman in a skin-tight, flesh-colored body suit, a high-kicker, a “hula-hula” dancer and the “coochie-coochie.” The police were on hand to stop any funny business; and a reporter was on hand to chronicle the madness; and the band played, “snatches from the coochie coochie,” suggesting that the song, “Poor Little Country Maid” may already have been known:

By midnight the grand ball room was brilliant with gay maskers. Capt. Pickett, who went into the Tenderloin with a determination to keep it straight, had his hands full from that time on, with his thirty-five uniformed men all over the place, to say nothing of the fifteen detectives up from Headquarters under Inspector McAvoy.

On they came, slender girls, buxom women and stalwart amazons, each vieing with her sisters in the liberality of her anatomical display. Indeed, one young person set out from the dressing-rooms in a suit of flesh-colored tights, sans everything in the way of trimming; no skirts, no trunks, not even a girdle – a veritable living picture. . . .

At 1 o’clock the dance music was a fashionable medley, including snatches from the “coochee-coochee,” and a score of women among the dancers “coochee-coocheed” spontaneously all over the ball-room – but only during the bars of the appropriate music. Then came a bit of Spanish music, and forty emulators of Carmeneta appeared, and then weird strains remindful of the “Midway” and there was “Hula-Hula” wriggling in every set, exciting and highly enjoyable for the “old boys” and the gilded youth, but bewildering to the sedate Capt. Pickett and his men. . . .

At 4 o’clock a wee little one in knickerbockers and answering to the name of “Gyp” “coochee-coocheed”and wriggled in a box to the delight of a coterie o men until a stern committeeman stopped her.

At 4.03 a slender young woman, whose perversity in high kicking had been repeatedly curbed, gave vent to her pent up exhileration by doing her “act” in the middle of the floor. Her limbs formed a straight line with a dainty slipper at either end. Then she was hustled away.

At 4.04 an amazon in baby blue tights wanted to punch her escort for spilling wine all over the blue nethers but was restrained.

At 5.10 the French ball for 1895 passed into history.

The Evening World (New York), February 12, 1895, page 3.

The “coochie coochee” music played at the masked ball may have been the popular song, “The Streets of Cairo; or The Poor Little Country Maid”; a song about a naïve young country girl who loses her innocence at the fair and gets a job, appearing “each night, in abbreviated clothes.”

The lyrics featured the now familiar expression, “kutchy, kutchy”:

She never saw the Streets of Cairo,

On the Midway she had never strayed,

She never saw the kutchy, kutchy,

Poor little country maid.[viii]

The same tune was published separately in 1895, as an instrumental called, “Kutchy Kutchy, or the Midway Dance.”

The iconic first five notes of the song (da-da-dah dah dah) are said to be identical to a French dancing song, “Colin Prend Sa Hotte,” which “appears in a French songbook from 1719”; and which, in turn, is nearly identical to “an Algerian or Arabic melody known as Kradoutja [that]has been popular in France since 1600.”

[ix]

The melody had also been associated with exotic dancers while the Chicago World’s Fair was still going on.

The theme appears in the “Persian Dancers” section of Gustav Luders’ 1893 composition, “An Afternoon in Midway Plaisance”

[x]; beginning in the fourth measure.

![]()

It may be only a coincidence, but the fact that the original title of the “kouta-kouta” dance melody was apparently “Kradoutja” in France makes me wonder.

Is “Kouta” a corruption of “Kradoutja”?

I don’t know, and there’s no other suggestion that it is.

But still, the fact that exotic, Middle Eastern dance forms were a hit in Paris before they came to the United States, and they knew the melody as “Kradoutja,” makes me wonder.

Of course, I do not know how well known “Kradoutja” was in France, or whether it was popularly associated with Middle Eastern dance there, so the jury is still out.

French linguists – a little help please.

But the first use of the expression, “Kouta-Kouta,” by the dancer “Avita,” who said that she learned the dance in India, may be more likely. (

See Part I).

By 1896, when Thomas Edison took time off from working on his nickel-a-view X-ray machine to film an exotic dancer doing the “coochie-coochie,” the expression “kouta-kouta” was nearly extinct:

X-Rays in a Slot Machine.

Drop a Nickel and See the Bones in Your Hand.

New York, March 29. – Thomas A. Edison ceased experimenting with X-rays today just long enough to see some Coochee-Coochee dancersphotographed for exhibition in his kinetoscope. Then he went back to his Crookes tubes and stayed at work all night, for his wife was away.

The wizard has almost completed another nickel-in-the-slot machine. You put your hand in a box containing X-rays and a fluorescent screen. Drop in a nickel and see the bones of your hand.

The Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, Hawaii), April 20, 1896, page 1.

Through the magic of Youtube – you can still see Edison’s Coochee-Coochee dancers (note, I do not vouch for the dates or titles; these are early images – but the dates, titles and places may be wrong):

The expression, “coochie-coochie” had a brief run of dominance, but “hoochie-coochie” was not far behind.

Hoochie-Coochie

The earliest examples of “hoochie-coochie” I could find date to 1896, in the title of another song about the fair, “When I Do the Hoochy Coochy in de Sky.” The lyrics refer several attractions from the World’s Fair and reflect the casually racist language of the day (“coon” and “nig”) – and again with the X-rays:

They’ll turn the X-rays on me when the music plays,

So dat ev’ry one can see into the dance,

I’m goin’ to do the coochy seven thousand diff’rent ways,

And I’ll knock the Midway people in a trance.

Oh, I have got a big balloon

With a seat for ev’ry coon,

So now ev’ry nig must either go or die;

Don’t you listen to strange rumors,

but go buy a pair of “bloomers,”

For to do the hoochy coochy in the sky![xi]

In 1904, The Colored American(a newspaper based in Washington DC) called the songwriter, Gussie L. Davis, “[t]he most famous Negro composer of popular songs”; so it is not immediately clear whether they lyrics pandered to white attitudes and tastes, or reflected common black usage of the time.

Music historian, Charles Kennedy, in his essay, “When Cairo Met Main Street” (included in the book,

Music and Culture in America, 1861-1918), places the expression, “hoochie coochie” (the dance) at Surf Avenue, Coney Island, in 1895

[xii]; which, if true, would make the expression older than the song, but still younger than “Kouta-Kouta” and “Coochie-Coochie.”

Charles Kennedy also postulated that “hoochy coochy,” in the context of the song, did not refer to the then popular dance, but harkened back to an early meaning of the words, related to the lyric, “hoochee koochee koochee,” in the song, “The Ham Fat Man,” a s

[xiii] I am inclined to disagree.

The song’s exhortation to “buy a pair of ‘bloomers,’ [f]or to do the hoochy coochy in the sky,” is a clear allusion to purchasing a loose-fitting pair of “harem pants,” now perhaps better known as

“Hammer” pants (as in M. C. Hammer); precisely the types of pants someone might wear to do a “hoochie-coochie” dance.

taple of minstrel shows in the 1860s.

But that is not to say that there is no connection between “hoochie-coochie” and “The Ham Fat Man.” The transition from “Kouta-Kouta” to “Coochie-Coochie” and “Hoochie-Coochie” may have been influenced by a general familiarity with the old Ham-Fat lyrics; and perhaps to more recent popular songs of the 1880s, like “Kutchy, Kutchy My Baby” (1884) and “Kutchy, Kutchy Coo!” (1888).

Kutchy Kutchy

The 1880s saw not one, but two popular songs with “Kutchy Kutchy” featured prominently in the title and lyrics. Based on the context of the lyrics, the expression appears to have been in use, as it is today, for talking to babies and as kissing-sound onomatopoeia.

In 1884, Nellie Cox scored a hit with “Kutchy Kutchy My Baby,” a song about the joys of parenthood and kissing the baby:

Oh, how I love the baby,

There’s nothing quite so sweet,

As the bright eyed little baby,

With chubby hands and feet . . . .

Kutchy, kutchy, kutchy, little baby,

Happy all the day,

Kiss your little hand to papa, da, da,

When he goes away . . .

In 1888, M. H. Rosenfeld, who also wrote, “Hush, Little Baby, Don’t You Cry,” wrote, “Kutchy, Kutchy, Coo!”; a song that presages Rupert Holmes’ late-1970s classic, Escape (The Pina Colada Song), by about ninety years.

A man and a woman, each cruising the street looking for a kiss-buddy (read, Victorian Tinder), find love – but inadvertently with their own spouse:

. . . As she pass’d along the street, Searching for a lover sweet,

“All I want is just a beau, To escort me to and fro” . . .

So he took this maiden fair, With her bangs and golden hair, Down the street to take a trip, Held her close and kiss’d her lips,

Tighter grew his fond embrace, Tho’ he scarce could see her face, For the night was very dark, And he tho’t it such a lark. . .

Goodness gracious, in the light, There he saw a fearful sight,

He was stabb’d as with a knife, Who d’ye think it was, his wife.

Chorus:

Kutchy, kutchy, kutchy, coo! Lovey me, I lovey ‘oo,

Kutchy, kutchy, kutchy coo! Lovey Lovey ‘oo!

Kutchy coo! (Kiss, kiss,) Kutchy coo! (Kiss, kiss,)

Kutchy coo! (Kiss, kiss,) Kutchy coo!

The composer claimed to have been inspired to write the song after hearing a passerby say, “Kutchy, kutchy, coo!!” to some young lovers kissing on the street.

“Kutchy, Kutchy Coo!” reached a wide audience. Newspapers in at least New York City and Boston published the complete sheet music, as a publishing gimmick to increase circulation:

Another evidence of the popularity of printing new music as a feature in daily journalism was evinced on Thursday, May 10th, by the publication in the Evening World of M. H. Rosenfeld’s song, “Kutchy, Kutchy, Coo!” a composition written originally for a soubrette and transferred to that newspaper. The music was reproduced from the original plate by the electro process, and presented a clean and admirable appearance, typographically. The Boston Globe also reprinted the composition on the following Sunday, issuing a large number of copies in excess of its regular edition.

Los Angeles Daily Herald, June 3, 1888, page 5.

If “Kutchy, Kutchy” was kissy-face, baby-talk nonsense in the 1880s, it may have been just rhyming, kissy-face nonsense in the 1860s, when “hootchy, cootchy, cootchy” is first attested – in the lyrics of “The Ham Fat Man.”

The Ham Fat Man

Both “hoochie-coochie” (derived from “coochie coochie”) and “coochie-coochie” (an altered form of kouta-kouta) may have been derived, at least in part, from a general familiarity with what was then a decades-old song lyric, “hootchy, kootchy, kootchy, I’m the Ham Fat Man.” “The Ham Fat Man” was a staple of black-face minstrelsy in the 1860s, but is best known today as the inspiration for the word “hamfatter,” later shortened to “ham,” meaning a bad actor.

The earliest reference I could find to the song is in a report of a military construction battalion of free black workers erecting the defenses around Baltimore during the American Civil War:

Several thousand hale, hearty and well-fed colored men, assured of receiving a fair compensation for their labors, are arduously engaged, and it is amusing to see the enthusiasm with which they discharge their duties. Whilst shoveling up the earth and erecting the barricades, they enjoy themselves by singing such songs as “When this Cruel War is Over,” “Coochee, Coochee, Coochee, the Ham Fat Man,” and other similar compositions, and they certainly have many star singers amongst them. They are all in high glee and in good spirits. – Balt. American.

The Daily National Republican(Washington DC), June 26, 1863, page 2.

At the time, the song was only a few years old.

The earliest indication of the song that I’ve found is an instruction to sing the early Civil War song, “The Union Man” (published in 1861) to the tune of “The Ham Fat Man.”

[xiv]

Although Baltimore’s construction battalion is quoted as having sung, “Coochee, Coochee, Coochee,” other published versions of the song, and later reminiscences of the song, generally recite the lyric, “hoochy, koochy, koochy” (or equivalent).

[xv] Alternate versions of the song, however, used “rooksey, cooksey, cooksey

[xvi]or “roochy coochy coochy.”

[xvii]

The song, or performers who sang the song, seem to have been wildly popular for a time; with several rival performers claiming to be the “original” “Ham Fat Man.” But by 1865, the song had already overstayed its welcome:

The beauty of [Billy Emerson’s] performance is that his songs are new; he has very wisely laid aside all such worn-out airs as “Uncle Snow,” “Ham Fat Man,” &c.

The New York Clipper, June 3, 1865, page 62.

The song was still well known in 1872, as evidenced by this story about a group of New Yorkers visiting St. Augustine and learning about Seminole history:

“Are you not thinking of the distinguished chieftains Holatoochee and Taholoochee, and the river Chattahoochee?” suggested John.

“For my part, I can’t think of any thing but the chorus of that classical song, The Ham-fat Man, ‘with a hoochee-koochee-koochee,’ you know,” whispered the Captain to Iris.

“Don’t I!” she answered. “I have a small brother who adores that melody, and plays it continually on his banjo.”

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 50, Number 245, December 1874, page 12.

The expression, if not the song, may also have been kept alive by the black-face comedian, “Billy” Rice, who is said to have been called “Hoochy-Coochy Rice because he often repeated the catch-phrase, “hoochy koochy,” when taking the stage. The nickname appears in a collection of stories collected at the Turnover Club, an actors’ social club in Chicago. The story ends in a joke about how Rice never had any of his own new material; precisely the sort of bad actor who might also have been called a “hamfatter” (bad actor):

‘Hoochy-Coochy Rice, the minstrel man – they always call Billy ‘Hoochy-Coochy,’ because he invariably says that whenever he comes on the stage – entered Hoyt’s room with a dark lantern and a jimmy and stole a new song which the author [(Hoyt)] had just written and nailed to the bedstead. I hardly believe this, though, as I have heard Billy Rice very often, and never knew of his having anything new.

William T. “Biff” Hall,

The Turnover Club,

Tales told at the meetings of the Turnover Club about actors and actresses, Chicago, Rand, McNally & Company, 1890, page 76.

[xviii]

If “Billy” Rice did sing the “Ham Fat Man,” he borrowed the song from someone else as well; he did not start his career until 1865, a few years after the song is known to have first been sung. When he died in 1902, he was remembered as one of the most famous of the dying breed of old-timey blackface minstrel comedians:

For more than a third of a century “Billy” Rice had made thousands of people forget their sorrow by his fun as a minstrel man “on the end.” Almost everybody has heard of “Billy” Rice, and most people who live in cities of the United States saw and heard him expound minstrel philosophy. In the old days he billed himself as “one hundred and ninety pounds of Rice,” and he lived up to his lithograph, particularly in the matter of weight.

The Topeka State Journal(Topeka, Kansas), March 3, 1902, page 2.

By 1903, with many of the old-time blackface performers dying away, the song may have reached such a level of obscurity that the origin of the term “hamfatter” (bad actor) was not widely known. An old-timer explained the origins of the term for a new generation:

Perhaps from the giving away of ham at Pastor’s the impression may prevail that that’s just how the term ‘hamfatter’ for a bad performer originated but this is not so.

The expression is an old minstrel term and came from the refrain of a song and dance which goes something like this: ‘Ham fat, ham fat, smoking in the pan.’ This song became popular, and the performers and later the public caught up the term. When a minstrel or a variety actor appeared and he was not up to the standard they used to yell at him, ‘Ham fat, ham fat, smoking in the pan.’ And this was abbreviated until poor actors were known as ‘hamfatters.’

The Rock Island Argus (Rock Island, Illinois), June 13, 1902 (reprint from the New York Sun).

Ham Fat Men

The “Ham Fat Man” was more than just a character in a minstrel show; he was based on an actual occupation.

Other occupations were also subject to parody by the minstrels.

One song book of the period

[xix], for example, has songs about, “The Soap Fat Man” (another name for the “ham fat man”), “The Stage Driver,” “The Pop-Corn Man,” “The Charcoal Man,” “The Rat-Catcher’s Daughter,” “The Shop Gals,” and “The Candle Maker’s Daughter.”

Not long since a class of traders called “soap fat men” used to go from house to house exchanging soap for the refuse fat accumulated by housewifes.

The Democrat (London), Volume 2, Number 23, December 5, 1885, page 178.

Soap-fat men, or ham-fat men, were at the low end of the food chain. Ham-fat men went door to door collecting leftover ham and bacon grease for delivery to a soap boiler. The soap boiler, in turn, made soap and tallow candles to be sold or traded back to the households donating the fat. A nostalgic piece from 1920 described the business as practiced in one neighborhood in Washington DC:

Who remembers the soap factory on the banks of Rock Creek at the terminus of Twenty-fifth and U streets, where you could take a quart bucket of grease and get a long bar of common soap, good for family washing, household scrubbing, etc?

The Washington Times(Washington DC), May 23, 1920, page 16.

A description of a poor neighborhood in which a quack doctor treated patients at the police station in the early 1800s lumps “soap-fat men” in with a number of other lowly trades:

These, however, were the aristocrats of my practice; the bulk of my patients were soap-fat men, rag-pickers, oystermen, hose-house bummers, and worse, with other and nameless trades, men and women, white, black, or mulatto.

The Century, volume 59, number 15, page 114.

A household-hints article from 1889, counseling housekeepers to cut out the middle-man and make their own soap:

Every economical housekeeper has her pot of “soap grease,”which, instead of trading it off with the soap man for soap, often of a poor grade, she makes into soft-soap.

The Iola Register (Iola, Kansas), May 17, 1889, page 7.

The soap boiler, the tradesman who created the soap and candles and who presumably stood a notch above the ham-fat man, were themselves considered a lowly profession. In 1864 a political hit-piece critical of former Louisiana Senator (and son of a “soap boiler”) John Slidell, played off his lowly “ham fat” beginnings:

A curious old assignment has been handed to the editors of the New York Evening Post dated April 20, 1824, by which it appears that John Slidell was in those days a tallow chandler! This John Slidell, insolvent soap boiler of 1824, was the father of John Slidell who in 1864 calls himself a Southern aristocrat, and whose daughter married a Parisian banker! Soap and tallow lard and ham fat!! Whew!!!

The Hillsdale Standard(Hillsdale, Michigan), November 29, 1864, page 1.

A soap boiler’s show was one feature used to highlight the low-class nature of a rough neighborhood in 1859:

[I]f the reader will endeavor to imagine a couple of oil-mills, a Peck-slip ferry-boat, a soap-and-candle manufactory, and three or four bone-boiling establishments being simmered together over a slow fire in his immediate vicinity, he may possibly arrive at a faint and distant notion of the greasy fragrance in which the abode of Madame Prewster is immersed.

Q. K. Philander Doesticks, The Witches of New York, Rudd & Carleton, 1859, page 41.

A handbook of soap chemistry, however, defended the honor of “soap boilers” – and recommended a more genteel title:

Thus, we have preferred the more unexceptionable expression savonnier to that of soap-boiler, which is stigmatized, however undeservedly, as harsh and opprobrious, and rather reproachful to the worthy operatives in this art.

Campbell Morfit, Chemistry Applied to the Manufacture of Soap and Candles, Philadelphia, Carey and Hart, 1847, page iv.

After the invention of margarine (“butterine”), the soap boilers another product to their line of goods:

If the “ham-fat man” brings in more grease than is wanted for soap the surplus can be made into butterine. If he brings in more than is wanted for butterine, the surplus can be turned into soap.

The Progressive Farmer, June 23, 1886, page 2.

But although “soap fat men” and “soap boilers” were considered to be a low, dirty job, some of them became a success.

William Colgate,

the founder of Colgate-Palmolive, started his career as a soap and candle maker.

If the title of “soap boiler” was “stigmatized . . . harsh and opprobrious,” the “ham fat man” must have fallen even lower on the scale.

But the “Ham Fat Man” did have one advantage; he had an opportunity to meet all of the women, cooks and kitchen staff in the neighborhood. Like the milk man of later generations, the “Ham-Fat Man” of song was a sort of neighborhood lothario; precisely the kind of man who might be the “someone in the kitchen with Dinah,” another staple of minstrel performances.

The Lyrics

The various versions of “The Ham-Fat Man” and “The Soap Fat Man” that I have seen, involve a relationship with someone on his fat-collection route. In “The Soap Fat Man,” which does not appear to be the same song, although it relates to a similar character, he seduces an “old maid” who is “fifty-six with a face of tan”; takes her to a “lager bier” garden; convinces her lend him $10 to open his own beer garden; and then absconds with the funds; as “he’d a wife and seven children, had the soap fat man.”

Two versions of “The Ham-Fat Man” may also offer a peek into social conditions that led to the development of so-called, “Soul Food;” traditional foods associated with African-American culture in the South. Although some features of soul food relate back to grains and vegetables brought over from Africa, other elements of soul food reflect the practice of slave “owners” feeding their captive workers as cheaply as possible. Slaves had to make do with what were considered less desirable “greens,” as well as less desirable cuts of meat. The “Ham-Fat” Man is satisfied with the fat of the ham; who needs veal, venison, chicken, hare or lamb:

Oh! good-ev'n to you, white folks,

I'm glad to see you all,

I'm right from ole Virginny,

Which some people say will fall;

You may talk about ole massa,

But he am just de man,

To make de n[-words] happy

Wid de ham-fat man.

Chorus.

Ham-fat, ham-fat, zig a zig a zam,

Ham-fat, ham-fat frying in de pan;

Oh! roll into de kitchen fast, boys, as you can,

Oh! rooksey, cooksey, cooksey, I'm de ham-fat man.

Ole missus she's up stair

A-eating bread and honey;

Massa's in de store

A-counting ob his money;

But Susan's in de kitchen

Frying at de ham,

And saving all de gravy

For de ham-fat man.-Chorus.

Some n[-words] likes de mutton,

Puddin', cakes and jam;

Some like veal and venison,

Chicken, hare and lamb.

But of all dese birds and beastesses

Dat plow the raging main,

Dey're not to be compared

To gravy in de pan - Chorus.

In this version, his relationship with Susan seems to be a good one; she saves her “gravy” and “ham fat” just for him, in what may be a mildly naughty sexual suggestion.

In another version, the “Ham Fat Man” is jealous of his rivals; and his “yaller gal’s” loyalty may be suspect:

When wittels am so plenty, oh! I bound to get my fill;

I know a pretty yaller gal, and I lover her to kill,

If any n[-word] fools wid her, I’ll tan him if I can,

A Hoochee, Koochee, Koochee, says the Hamfat man.

A third version of the song involves a more brazen cheater, who leaves town with an Asian man:

White folks attention, and listen to my song

I’ll sing to you a ditty and it won’t detain you long

It’s all about a pretty girl, whose name was Sara Ann

And she fell deep in love with the ham fat man.

Ham fat, soap fat, candle fat or lard,

Ham fat, cat fat, or any other man,

Jump into the kitchen as quick as you can,

With my roochee, coochee, coochee, the ham fat man.

Now the ham fat man, he couldn't stand the press

For every day she wanted to buy a new dress

His money it was gone and the faithless Sara Ann

She hooked it off to Bathurst with a Chinaman

Elements of the second and third versions point to another early influence on the song; a traditional Irish song called, “The Cuckoo’s Nest.” Both versions are about a woman who is, or may be, unfaithful, and the third version, from Australia, is said to be sung to the tune of “The Cuckoo’s Nest.”

The connection is plausible.

Although a musicologist might see it differently, you can make your own judgment.

Listen to the Australian version here– and compare it to this version of “The Ham Fat Man” melody; there is a marked similarity, particularly in the chorus, which begins in the second line:

The chorus sounds an awful lot like the “Oompah, Loompah” song from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Compare . . .

Oompa Loompa doom-pa-dee-do . . .

. . . with several variations of “The Ham Fat Man” chorus . . .

Ham-fat, ham-fat, zig a zig a zam . . .

Ham-fat, ham-fat, fryin’ in de pan . . .

Ham-fat, ham-fat, candle-fat and lard . . .

The “coochie” and “cooksey” elements of the songs could also relate back to “cuckoo’s nest”; or, it may just all be a big coincidence.

But the melodic and rhythmic similarities seem strong.

Other traditional melodies and songs were also the result of decades of evolution and borrowing a melody here, a theme there, and another lyric over there.

See, for example, my earlier post on

the history of the beloved Irish ballad, Cockles and Mussels or Molly Malone.

H-Word Rhyming Reduplication

The transition of Coochie-Coochie to Hoochie-Coochie may also have been influenced by a linguistic template that favors rhyming reduplication words beginning with the letter H. The linguist, lexicographer and language commentator, Ben Zimmer, for example, pointed out that:

A lot of these [rhyming reduplication words] in English start with the letter H, and very often they are words that connote [(or evoke)] recklessness – chaos: Helter-skelter, harum-scarum, higgledy-piggledy, hugger-mugger, hodge-podge, hurly-burly . . . hurdy-gurdy, hocus-pocus.”

Once one or two of these get planted in the language, it kind of sets the template for others to follow.

Slate.com podcast, Lexicon Valley (Episode No. 65), “The Jittery History of a Very Nervous Phrase [(Heebie Jeebies)], July 27, 2015.

Several H-word, rhyming reduplication expressions for seemingly reckless or chaotic dances (at least by American puritanical tastes) pre-date “Hoochie-Coochie” as the name of the dance. “Hurdy-Gurdy” (dance halls in American mining camps), “Honky-Tonk” (dance halls along cattle-drive trails between Oklahoma and Texas) and the Hawaiian “Hula-Hula,” for example, were all in use before “Kouta-Kouta” evolved into “Hoochie-Coochie.”

“Hurdy Gurdy,” originally a name for a hand-cranked musical instrument, was a common name of a dance hall in mining camps of the American West, from as early as 1864:

About 12 o’clock last Saturday night, a row occurred in the Hurdy Gurdy house on Main street, formerly known as the Idaho Restaurant, between Tom Wilson and a butcher from Romer & Collen’s market . . .

Boise News (Bannock City, Idaho), July 23, 1864, page 2.

In 1865, Virginia City, Montana issued an ordinance to regulate “Dance or Hurdy Gurdy Houses.”

[xx] In 1889, when the danse du ventre was making a sensation at the Paris World’s Fair, American humorist Bill Nye (not the science guy) compared the American “Hurdy-Gurdy” and the Continental “Can-Can” to the “Algerian Stomach Dance.”

“Hurdy-Gurdies” and “Hurdy-Gurdy Girls” were still a familiar feature of life in mining camps during the Yukon gold rush in the late-1890s:

“Honky-Tonk,” first attested in 1889, first appears regularly in newspapers in cities along the long cattle drive routes between Oklahoma and Texas.

“Hula-Hula,” is admittedly not an English word, but the reduplication of “hula” may be American.

“Hula-hula” appears in print in American newspapers as early as 1860

[xxi]; but generally appears as only “hula” or “hula dance,” in English language newspapers published in Hawaii.

There were some exceptions, but even then, it is difficult to determine whether it reflects the usage of an Anglo-American immigrant or local tradition.

In any case, “hula-hula” was a known name for a seemingly chaotic dance form that was known before the “Kouta-Kouta” evolved into “Hoochie-Coochie.”

The linguistic template favoring H-word rhyming reduplication may have influenced the creation and/or acceptance of “Hurdy-Gurdy,” “Honky-Tonk,” “Hula-Hula,” and “Hoochie-Coochie” into the language.

![]() |

| Harper’s, volume 47, number 280, September, 1873, page 548. |

Little Egypt

“Little Egypt”, who caused all of the commotion at the Seeley Dinner (

see Part I), does not appear in the written record, at least by that name, before or during the Chicago World’s Fair.

Donna Carlton devoted an entire book (

Looking for Little Egypt (1995)) to the search for evidence of Little Egypt at the Chicago World’s Fair, and apparently found none.

It is possible that she danced at the fair under a different name, or in relative anonymity, since her name (or at least a dancer with the same stage name) does appear in print less than three weeks after the Chicago Fair closed, and less than two weeks before the post-World’s Fair Exhibition opened in New York City.

She performed with the Empire Gaiety Company, alongside Mahomet, “the educated horse,” S. H. Burton, and his dog circus, and others, at Proctor’s in New York.

[xxii]

“Little Egypt” also appeared at a second “miniature Midway Plaisance” at the Convention Hall in New York City in April, 1894, with Fatima in Brooklyn in June 1894 (“When it was all over the men looked at each other sheepishly and the women spectators hurried out”), at the St. Louis Fair in August, 1894, and again with Fatima in New York City, as part of Reilly & Wood’s Big Show (the same troupe that Avita performed with in 1892 and 1893). She did not become a household name until after her sensational arrest during the Seeley Dinner in December 1896.

![]()

“Little Egypt,” who was identified as Ashea Wabe in court following the Seeley Dinner, but whose real name was apparently Catherine Devine, parlayed her notoriety into a sizeable fortune. She married well too; to a man named Frederick Hamlin, the scion of a New York banking family; but she never saw any of his money. The marriage was not known publicly until after her death; and they had been estranged since shortly after their marriage due to his family’s opposition to her notorious reputation. A few weeks before her death, he reportedly asked her for a divorce so that he could marry a clergyman’s daughter. And when she died under suspicious circumstances before the divorce was ever finalized; he came out of the woodwork to file papers to gain control over her $100,000 estate – I say he was a good banker, not a good man:

“Little Egypt,” the dancer who, unclad, save for a few almost superfluous pieces of gauze, danced before the diners the “danse du ventre” or “hootchy kootchy” . . . was found dead in her room under mysterious circumstances. . . . She lay as though she had been carelessly flung across the bed. Her left hand was tightly clenched. Her mouth, from which blood had poured, was wide open, as though she had died screaming for help. On her throat were livid marks like the imprint of murderers’ fingers. No one was able to tell who or what had caused her death.

![]()

In the interest of completeness, I feel compelled to note a possible influence on her chosen stage name, “Little Egypt.”

Although it could have been a reference to the miniature Street of Cairo exhibition (analogous, perhaps, to

Wee Britain in Arrested Development), it may also have been a reference to a purported, traditional name for the “kingdom” of Gypsies in England and Scotland, “Little Egypt.”

In 1892, Edgar Wakeman published an essay on the history of Gypsies in Britain, in which he shared historical stories about Anthnonius Gawino, “Earl of Little Egypt” in the early 1500s, and John Faw, “Lord and Earl of Little Egypt” in the mid-1500s.

The word “Gypsy” was purportedly derived from “Egypt,” reflecting the notion that they were descended from Middle Easterners.

The essay, which was widely reprinted in numerous newspapers across the United States, may have inspired S. R. Crockett’s well advertised book,

The Raiders, Being Some Passages in the Life of John Faa, Lord and Earl of Little Egypt, which was published in early 1894.

It seems plausible that “Little Egypt” could have been similarly inspired to adopt the name as her own.

Years later, her fame was still such that a fish lure manufacturer named its “wiggling” worm lure after her:

Summary

The expression, “hoochie, coochie, coochie,” dates to at least the early 1860s, as an apparently nonsense lyric in the popular minstrel song, “The Ham Fat Man.” The expression may have been influenced by an older, melodically and rhythmically similar song, “The Cuckoo’s Nest.” It may also have been understood as a kissing sound (as it would be later in the popular songs, “Kutchy, Kutchy, My Baby,” and “Kutchy, Kutchy, Coo!”), since the ham-fat man of the song generally had some sort of sumpin’-sumpin’ going on with someone.

The “Eastern” dance style popularized at the Paris World’s Fair in 1889 and Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 is not known to have been called the “coochie-coochie” or “hoochie-coochie” until a year or two after the fair closed. The dancer, “Avita” (or “Vita”) introduced the “Kouta-Kouta” dance on Broadway in 1892, in the harem scene of the play, Elysium. She claims to have learned the dance in India, where the word, “Kouta” is known to have been the name of a “quick style of dance” as early as 1858. Avita toured the United States for at least a year, performing the “Kouta-Kouta” in New York, Indianapolis, and Washington DC, before taking the dance to London in early 1894, just a few months after the Chicago World’s Fair closed.

The dance name, “Kouta-Kouta, became associated, generally, with dancing at the Chicago World’s Fair before it closed in October, 1893. By mid-1894, the “Kouta-Kouta” had made news in all corners of the country, usually in association with dancers said to have performed at the Midway Plaisance at the Chicago World’s Fair. The name, “Coochie-Coochie,” first appeared in association with the dance in late-1894; and the name, “Hoochie-Coochie,” appeared about one year later. By the end of 1896, the names, “Coochie-Coochie” and “Hoochie-Coochie” had nearly erased Avita’s “Kouta-Kouta” from the popular lexicon.

[ii]The Sun (New York), December 4, 1893, page 3 (the woman at the Imperial Palace is more suggestive and bold);

The Evening World (New York), December 5, 1893, page 6 (Omene appearing on the bill at the Imperial Palace).

[iii]New York Clipper, March 24, 1894, page 38 (Bryant & Richmond’s Vaudevilles drew to good attendance.

The Kouta Kouta Dancers were a feature.).

[iv]Boot and Shoe Recorder, volume 26, October 10, 1894, page 117.

[v]Evening Star (Washington DC), August 27, 1895, page 12 (Florence Miller made a hit with her songs and her kouta-kouta dance).

[vi]New York Clipper, November 9, 1895, page 567 (Moorish dancers, in their kouta-kouta dance, will be the principal feature for the current week).

[viii]“The Streets of Cairo; or the Poor Little Country Maid,” written and composed by James Thornton, New York, Frank Harding, 1895, (Johns Hopkins, Sheridan Libraries Special Collections, The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Box 144, Item 23).

[x]“An Afternoon in Midway Plaisance, Fantasie for Piano by Gustav Luders, as played with phenomenal success by the Schiller Theatre Orchestra,” Chicago, Henry Detmer Music House, 1893 (Johns Hopkins, Sheridan Libraries Special Collections, The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Box 170, Item 4).

[xii]Michael Saffle and James Heintze,

Music and Culture in America, 1861-1918, London and New York, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 1998, pages 280-281, footnote 30 (citing Edo McCullough’s history of Coney Island).

[xiii]Michael Saffle and James Heintze,

Music and Culture in America, 1861-1918, London and New York, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 1998, page 278.

[xiv]Songs for the Union, Philadelphia, A. Winch, 1861, page 32.

[xix]Billy Birch’s Ethiopian Melodist, New York, Dick & Fitzgerald, 1863.

[xx]The Montana Post (Virginia City, Montana), February 25, 1865, page 3.

[xxi]The Union County Star and Lewisburg Chronicle (Lewisburg, Pennsylvania), June 22, 1860, page 1 (“

wahine hula-hula (singing woman)).”

[xxii]The Evening World (New York), November 18, 1893, page 5.